The Amazon rainforest is one of the planet’s best natural climate solutions. Roughly 123 billion tons of carbon are estimated to be stored in the trees and soils of the Amazon and, if protected, it has the power to continue sequestering billions of tons of carbon each year.

But that irreplaceable carbon sink is under steady threat from a cycle of deforestation, fire, and drought that is both exacerbated by and contributing to climate change. Preliminary analysis from Woodwell of last year’s data has outlined that the most vulnerable regions of the Amazon are where drought and deforestation overlap.

2021 data shows deforestation drives fire in the Amazon

Unlike temperate or boreal forest ecosystems—or even neighboring biomes in Brazil— fires in the Amazon are almost entirely human caused. Fire is an intrinsic part of the deforestation process, usually set to clear the forest for use as pasture or cropland. Because of this, data on deforestation can provide a good indicator of where ignitions are likely to happen. Drought fans those flames, producing the right conditions for more intense fires that last longer and spread farther. Examining the intersection between drought and deforestation in 2021, Woodwell identified areas of the Amazon most vulnerable to burning.

Areas of deforestation combined with exceptionally dry weather to create high fire risk in northwestern Mato Grosso, eastern Acre, and Rondonia. Although drought conditions shifted across the region throughout the course of the year, deforestation caused fuel to accumulate along the boundaries of protected and agricultural land.

These areas of concentrated fuel showed the most overlap with fires in 2021, indicating that without the ignition source that deforestation provides, fires would be unable to occur, even during times of drought.

In June of 2021, we identified a dangerous and flammable combination of cut, unburned wood and high drought in the municipality of Lábrea, that put it at extreme risk of burning. Data at the end of December of 2021 confirmed this prediction. The observed fire count numbers from NASA showed that last year, Lábrea experienced its worst fire season since 2012.

Fires and climate change form a dangerous feedback loop

As a result of deforestation in 2021, at least 75 million tons of carbon were committed to being released from the Amazon. When that cut forest is also burned, most of the carbon enters the atmosphere in a matter of days or weeks, rather than the longer release that comes from decay.

This fuels warming, which feeds back into the cycle of fire by creating hotter, drier, conditions in a forest accustomed to moisture. Drought conditions weaken unburned forests, especially around the edges of deforestation, which makes them more susceptible to burning and releasing even more carbon to the atmosphere to further fuel warming.

Fire prevention strategies enacted by the current administration over the past 3 years have been insufficient to curb burning in the Amazon, because the underlying cause of deforestation remains unaddressed. Firefighting crews are not sufficiently supported to continue their work in regions like Lábrea that are actively hostile to combating deforestation and fire. If deforestation has occurred, fire will follow. To ensure the safety of both the people and the forests in these high-risk municipalities, the root causes of deforestation must be addressed with stronger and more strategic policies and enforcement.

Woodwell workshop brings Indigenous firefighters to Brasilia

A week-long workshop encourages knowledge sharing between Indigenous Brazilian fire brigades

On March 28, 2022, firefighters from Indigenous communities across Brazil gathered in Brasília, the country’s capitol, for a week-long geography and cartography workshop. The workshop, a collaboration between the Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB) and the Amazon River Basin (COICA), IPAM Amazônia, and Woodwell Climate Research Center, walked participants through the basics of using Global Information Systems technology to monitor and manage their own lands and forests.

Forests and native vegetation on Indigenous lands have been sustainably managed for millenia, and studies have found Indigenous stewardship of forests is an effective measure for preventing deforestation and degradation. Escaped fires can present a threat to forests, and many Indigenous communities have their own brigades that work on detecting and preventing runaway fires. In some places, prescribed burns are used as a tool for shaping and cultivating the land.

Participants attended from Indigenous lands located in a variety of Brazilian landscapes—from the Cerrado to the heart of the Amazon. Despite differences, participants found learning from other Indigenous communities extremely valuable.

“People came with a variety of skill sets,” said Woodwell Water Program Director Dr. Marcia Macedo. “What was most meaningful for participants was seeing other people like them, who do the same work and are also Indigenous people, already dominating material, knowing how to make the maps, and helping others. It gave them confidence that they could also figure it out.”

After a day of introduction to the core concepts of GIS and mapping, participants headed out to Brasília National Park to test their newfound skills. They visited burned areas from both an escaped fire and a prescribed burn, compared the two, marked GPS points, and took pictures. The data gathered on the field trip was used over the next few days to practice making maps.

“The goal was to not only teach the theory and help them understand the steps for making maps, but also mainly to develop the skills for them to be able to apply to their own lands on their own time,” said Woodwell postdoctoral researcher, Dr. Manoela Machado, who helped organize the event.

The workshop also fostered discussions about the complexity of management when fire can be both a threat and a tool. Because fire manifests differently in different biomes, well-managed fires look different for each community.

“On the final day, we had a discussion of values. Is fire good or bad? For whom—ants, forests, human health?” said Dr. Machado. “You can’t just criminalize fire if it’s a part of traditional knowledge and used as a tool for providing food, for example. So it’s a complex issue.”

Dr. Machado hopes the conversations will continue. She says the goal would be to host this workshop again to expand its reach, potentially beyond Brazil to include participants in other Amazonian countries.

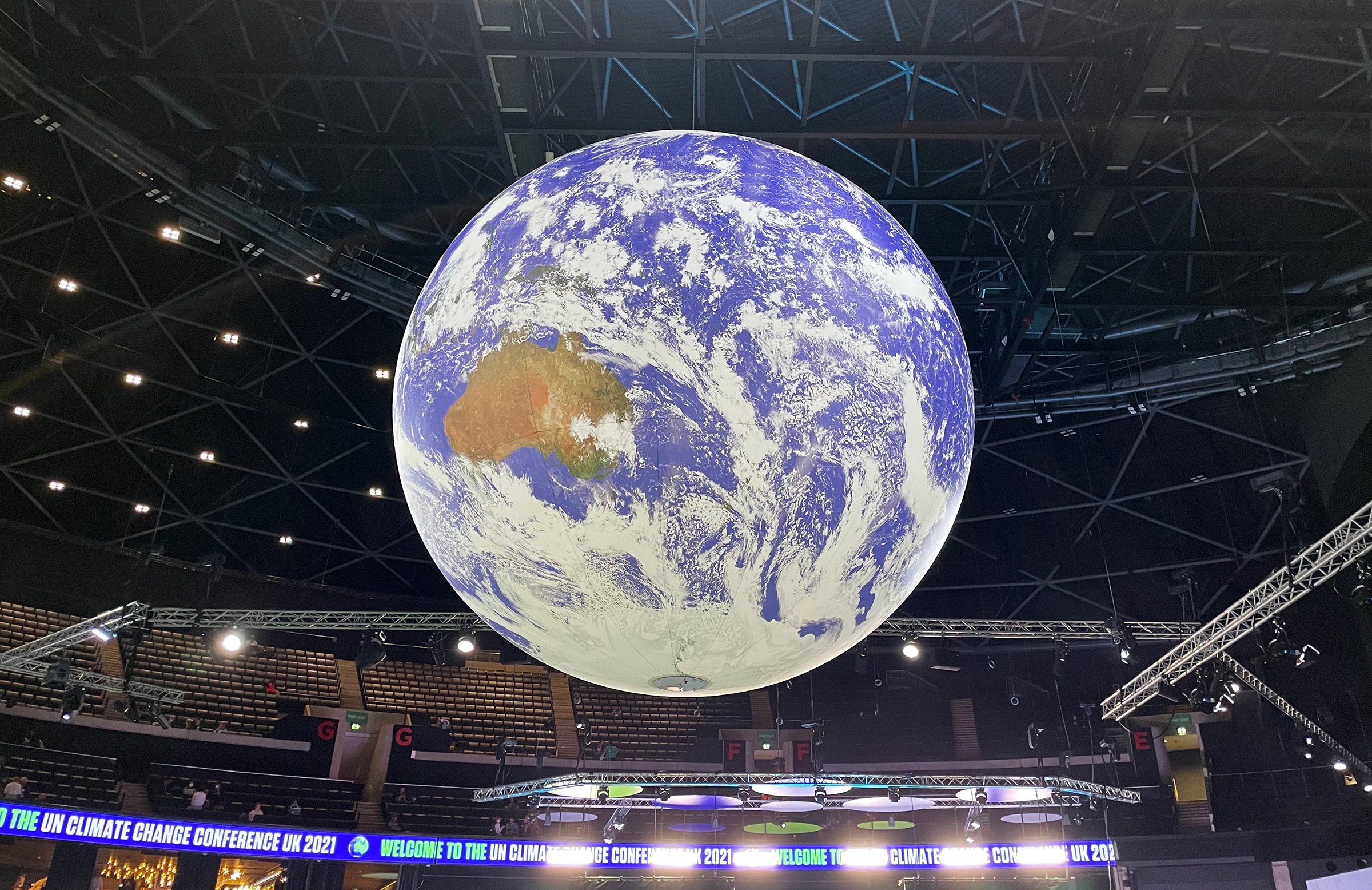

Success or failure? Woodwell scientists deem COP26 a mixed bag

Glasgow Climate Pact alone is not enough to limit warming to 1.5 C, but COP26 made real progress

For the first two weeks of November, diplomats and scientists from around the world descended on Glasgow, Scotland for the United Nations’ 26th annual Conference of Parties—hailed by some as the “last, best, hope” for successful international cooperation on the issue of climate change. Woodwell sent three expert teams to push for more ambitious policies that integrate our understanding of permafrost thaw and socioeconomic risks, and for financial mechanisms to scale natural climate solutions. Here are their thoughts on the successes and failures of this pivotal meeting.

Bold pledges but uncertain follow-through for tropical forests

The conference started off with a bold promise from 100 nations to end deforestation by 2030, accompanied by a pledge of more than $19 billion from both governments and the private sector. Though similar pledges to end deforestation have failed in the past, the funding pledged alongside this one gives reason to be hopeful.

$1.7 billion of the funds are allocated specifically to support Indigenous communities, which Woodwell Assistant Scientist Dr. Glenn Bush believes is a big step forward, though creating policies that are equally supportive will be where the real work gets done.

“It’s particularly welcome that Indigenous peoples are finally being acknowledged as key protectors of forests. The real challenge, however, is how to deliver interlocking policies and actions that really do drive down deforestation globally and scale up nature-based solutions to climate change.”

Dr. Ane Alencar, Director of Science at IPAM Amazônia, said that, for Brazil, half of the solution could come from enforcing existing laws and designating public forests. The other half could come from consolidating protected areas, creating incentives for private land conservation, and providing technical support for sustainable food production.

Dr. Bush also presented the CONSERV project, a joint initiative between IPAM and Woodwell that provides compensation for farmers who preserve forests on their land, above and beyond their legal conservation requirements. Increasing the scale and financing of viable carbon market plans like CONSERV could be crucial in incentivizing greater forest protection.

Climate risk a growing focus for governments

During the second week of the conference, Woodwell released a summary report on a series of climate risk workshops with policymakers and climate risk experts from 13 G20 nations. These workshops, conducted in collaboration with the COP26 Presidency and the British government’s Science and Innovation Network, identified challenges to incorporating climate risk assessments into national-level policy, and the report made recommendations for moving from simply making the science available to making it useful for implementation. The report demonstrated a desire from policymakers to get involved in climate risk analyses early in the process, to ensure the information addresses a country’s particular needs.

One success of the conference was the creation of a new climate risk coalition, led by Woodwell. The coalition, composed of 9 other organizations, will produce an annual climate risk assessment for policymakers.

“Understanding the full picture of climate risk is incredibly important when you’re setting policy,” explained Woodwell’s Chief of External Affairs, Dave McGlinchey. “We also heard, however, that the climate risk assessments need to be designed with the policymakers who will eventually use them. This research must speak directly to their interests if it is going to be delivered effectively.”

The increased desire of policymakers to better understand and address oncoming climate risks demonstrates an important shift to viewing climate change as a present problem, rather than solely a future one.

Permafrost thaw presents the greatest remaining uncertainty in forecasting emissions

One risk that still isn’t high enough on the COP agenda is rapid Arctic change, particularly permafrost thaw. The Cryosphere Pavilion, hosted by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, convened conversations ranging from the implications of permafrost thaw, to environmental justice for Northern Communities and respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture. For Arctic Program Director, Dr. Sue Natali, the Indigenous-led panels were some of the most impactful of the conference. But postdoctoral researcher Dr. Rachael Treharne noted that, no matter how well attended, there’s a difference between being in the Cryosphere Pavilion and being on the main stage.

Woodwell was among a group of organizations pushing to get permafrost emissions the attention it demands. Emissions released by thawing permafrost are currently not accounted for in national commitments, but are potentially equivalent to top emitting countries like the U.S. November 4 at the conference was “Permafrost Day” and each event was at full capacity for the pavilion, signaling growing attention to permafrost science. Woodwell, alongside a dozen polar and mountain interest groups called for even more commitment to the cryosphere conversation at the upcoming Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice U.N. climate conference in Bonn scheduled for June of 2022.

Even with this greater recognition of the seriousness of Arctic climate change, the region and its people are being hit much harder and faster than the rest of the globe. Slow-moving decision-making and talk without follow-through will seriously endanger Arctic residents.

“I left the COP having a very hard time feeling ‘optimistic’, while knowing that the hazards of climate change are already severely impacting Arctic lands, cultural resources, food and water security, infrastructure, homes, and ways of living,” said Dr. Natali. “After repeated years of record-breaking Arctic wildfires, heatwaves, and ice loss, I’m not sure how a 1.5 or 2C warmer world—one in which we know that these events will only get worse—is a reasonable goal.”

Though missing necessary milestones at COP26, climate action is accelerating

Overall, however, the final Glasgow Climate Pact fell short of the ambitious action the world needs in order to limit warming. The deal made several last-minute compromises surrounding the phase out of fossil fuels. COP president Alok Sharma said that, while a future with only 1.5 degrees of warming is possible, it is fragile—dependent on countries keeping to their promises.

Despite this, McGlinchey says there was real progress at COP26. The conference reached a resolution that earned the unanimous agreement of all attending parties. The formal process has also begun to accelerate, with nations required to return with more ambitious climate mitigation plans next year, rather than on the previous five year timeline.

“We are not yet where we need to be,” McGlinchey said. “But we are better off than where we were two weeks ago. Let’s keep going.”

a