Though droughts and bad harvest years are occasional risks for farmers, modern agriculture is built on the assumption of a predictable and stable climate. Rising temperatures are breaking down that assumption, leaving the future of food uncertain. Two new studies put the increasing risks in sharp relief.

Seventy-two percent of today’s staple crops—maize, wheat, soybeans and rice—are grown in just 5 countries, in regions of the world known as breadbaskets. From the plains of North America to the river valleys of India and China, these regions earned their distinction for supporting hundreds of years of agricultural production with their climatic suitability.

“These regions have developed this way for centuries in the same way that human settlements have developed around water, because that’s where the resource was,” says Woodwell Research Assistant, Monica Caparas.

Caparas works on agricultural risk models. Last year, she led an analysis of crop failures in global breadbaskets, projecting the likelihood of declining yields in the upcoming decades. Her results conjured a world where these centuries-old food producing regions may no longer be so reliable. By 2030, crop yield failures will be 4.5 times higher. By 2050, the likelihood shoots up to 25 times current rates.

By mid-century, the world could be facing a rice or wheat failure every other year, with the probability of soybean and maize failures even higher. A synchronized failure across all four crops becomes a possibility every 11 years.

If that sounds like rapid, drastic change, that’s because it is. The immediacy of increasing failures surprised even Caparas.

“The fact that by 2050—which we are almost halfway to already— there could be a wheat failure every year. It’s startling.”

One major component of crop failure predictions is water scarcity. In a warmer world, water is a critical resource. Climate change will shift precipitation patterns, drying out some regions and inundating others. Most of the world’s breadbaskets are headed in the drier direction.

Caparas factored water availability into her analysis, finding the likelihood of crop failure much higher in water scarce sections of breadbaskets. Wheat is especially water dependent, particularly in India where 97% of wheat crops are growing in areas already experiencing water stress. Irrigation could make up for some lack of rain, but groundwater stores are already overdrawn in many places.

Farms beginning to feel the impacts of climate change in Brazil

In Brazil, agriculture is already showing signs of declining productivity from changing precipitation. Woodwell Assistant Scientist Dr. Ludmila Rattis works in Mato Grosso, where she researches the impacts of agriculture and deforestation on the regional climate. Central Brazil is a major breadbasket for soybeans and maize—as well as cattle— and as crop demand increases, farms and ranches have advanced into the Amazon rainforest and the Cerrado, the Brazilian Savanna.

Clearing and burning forests not only releases carbon that contributes to rising global temperatures, it can also have drying effects on the local watershed. In recent years, farmers in Mato Grosso and the Cerrado have reported issues with dry spells, though they would not attribute it to climate change. Dr. Rattis wanted to quantify these anecdotes to show that they were connected.

“I was trying to see why they were denying the climate changing at the same time they were feeling the climate changing. Were they feeling that in their pockets? Was it affecting the finance of their business?”

Dr. Rattis modeled temperature and precipitation changes along Brazil’s Amazon-Cerrado frontier. Her results not only predicted that by 2060, 74% of the region’s agricultural land would fall outside of the ideal range of suitability for rainfed agriculture, they showed that nearly a third of farms already did.

The changes are affecting crop productivity. When the temperature gets warmer, plants grow faster, releasing more water vapor into the air from their leaves as a byproduct of photosynthesis. If there isn’t a steady supply of soil moisture available to replace the lost water, plant growth is stunted. Rainy seasons are also starting later, limiting the possibility for planting two rounds of crops in a single season, which cuts into farmer’s profits and encourages further expansion via land clearing.

Ideal climate for agriculture migrating north

Caparas notes that increasing crop failure doesn’t necessarily mean we are headed for a world without maize or soybean. But it does mean a drastically different agricultural system— one where hard decisions have to be made about land use.

“Increasing crop failures doesn’t mean that these crops won’t ever be able to grow in these areas again, or that they should be abandoned, just that it’s going to be much harder for them to be as productive,” Capraras says. “There might be a certain threshold of losses that would lead people to leave these croplands.”

There is some potential for migration of the most productive lands as northern latitudes begin to warm. Caparas’s projections showed the greatest likelihood of breadbasket migration from the United States into Canada.

However, just because the climate suitability is migrating, doesn’t mean agricultural production will shift along with it. Other factors including soil fertility or existing land uses could limit the practicality of moving to new regions, especially if it jeopardizes existing climate solutions as the case in Brazil has shown. Clearing forests is only accelerating warming, drought and declining productivity.

Future of food depends on drought resilience

Shoring up food security in a changing climate will require system-wide changes to our current agricultural system. Part of that starts with adjusting farming strategies to mitigate the effects of the warming that’s already unavoidable. Dr. Rattis has begun outreach to the farmers whose land she collected data on, giving them a picture of what their farms will look like if nothing changes.

“We need to make them feel that they’re part of the research, because they are. If we do, once we get the results, the probability of them using those results to adapt the way that they produce food will increase,” Dr. Rattis says. “They can see themselves in the historic part of the graphic and then I show them where, climatically speaking, their farm is going,”

She’s hoping these conversations will open Brazil’s farmers up to practices that leave more native vegetation on the landscape, which would help stabilize the local climate and keep the natural watershed intact.

Caparas takes hope from the fact that the outcomes of her models are not set in stone. In the planet-wide experiment of climate change, we can affect the results.

“These projections are due to changes in climate. They don’t account for adaptation strategies. The agricultural technology industry is fast-growing and so I think that there is hope, as long as adaptation techniques are implemented equitably,” Caparas says.

Much of the innovation, Caparas says, will have to involve developing drought resistant crop varieties and less water intensive agricultural processes. In the long term however, securing a productive agricultural future for the Earth’s nearly 10 billion people by 2050 will depend on securing a stable climate.

“First and foremost it always has to be getting climate change in check,” says Caparas.

Success or failure? Woodwell scientists deem COP26 a mixed bag

Glasgow Climate Pact alone is not enough to limit warming to 1.5 C, but COP26 made real progress

For the first two weeks of November, diplomats and scientists from around the world descended on Glasgow, Scotland for the United Nations’ 26th annual Conference of Parties—hailed by some as the “last, best, hope” for successful international cooperation on the issue of climate change. Woodwell sent three expert teams to push for more ambitious policies that integrate our understanding of permafrost thaw and socioeconomic risks, and for financial mechanisms to scale natural climate solutions. Here are their thoughts on the successes and failures of this pivotal meeting.

Bold pledges but uncertain follow-through for tropical forests

The conference started off with a bold promise from 100 nations to end deforestation by 2030, accompanied by a pledge of more than $19 billion from both governments and the private sector. Though similar pledges to end deforestation have failed in the past, the funding pledged alongside this one gives reason to be hopeful.

$1.7 billion of the funds are allocated specifically to support Indigenous communities, which Woodwell Assistant Scientist Dr. Glenn Bush believes is a big step forward, though creating policies that are equally supportive will be where the real work gets done.

“It’s particularly welcome that Indigenous peoples are finally being acknowledged as key protectors of forests. The real challenge, however, is how to deliver interlocking policies and actions that really do drive down deforestation globally and scale up nature-based solutions to climate change.”

Dr. Ane Alencar, Director of Science at IPAM Amazônia, said that, for Brazil, half of the solution could come from enforcing existing laws and designating public forests. The other half could come from consolidating protected areas, creating incentives for private land conservation, and providing technical support for sustainable food production.

Dr. Bush also presented the CONSERV project, a joint initiative between IPAM and Woodwell that provides compensation for farmers who preserve forests on their land, above and beyond their legal conservation requirements. Increasing the scale and financing of viable carbon market plans like CONSERV could be crucial in incentivizing greater forest protection.

Climate risk a growing focus for governments

During the second week of the conference, Woodwell released a summary report on a series of climate risk workshops with policymakers and climate risk experts from 13 G20 nations. These workshops, conducted in collaboration with the COP26 Presidency and the British government’s Science and Innovation Network, identified challenges to incorporating climate risk assessments into national-level policy, and the report made recommendations for moving from simply making the science available to making it useful for implementation. The report demonstrated a desire from policymakers to get involved in climate risk analyses early in the process, to ensure the information addresses a country’s particular needs.

One success of the conference was the creation of a new climate risk coalition, led by Woodwell. The coalition, composed of 9 other organizations, will produce an annual climate risk assessment for policymakers.

“Understanding the full picture of climate risk is incredibly important when you’re setting policy,” explained Woodwell’s Chief of External Affairs, Dave McGlinchey. “We also heard, however, that the climate risk assessments need to be designed with the policymakers who will eventually use them. This research must speak directly to their interests if it is going to be delivered effectively.”

The increased desire of policymakers to better understand and address oncoming climate risks demonstrates an important shift to viewing climate change as a present problem, rather than solely a future one.

Permafrost thaw presents the greatest remaining uncertainty in forecasting emissions

One risk that still isn’t high enough on the COP agenda is rapid Arctic change, particularly permafrost thaw. The Cryosphere Pavilion, hosted by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, convened conversations ranging from the implications of permafrost thaw, to environmental justice for Northern Communities and respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture. For Arctic Program Director, Dr. Sue Natali, the Indigenous-led panels were some of the most impactful of the conference. But postdoctoral researcher Dr. Rachael Treharne noted that, no matter how well attended, there’s a difference between being in the Cryosphere Pavilion and being on the main stage.

Woodwell was among a group of organizations pushing to get permafrost emissions the attention it demands. Emissions released by thawing permafrost are currently not accounted for in national commitments, but are potentially equivalent to top emitting countries like the U.S. November 4 at the conference was “Permafrost Day” and each event was at full capacity for the pavilion, signaling growing attention to permafrost science. Woodwell, alongside a dozen polar and mountain interest groups called for even more commitment to the cryosphere conversation at the upcoming Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice U.N. climate conference in Bonn scheduled for June of 2022.

Even with this greater recognition of the seriousness of Arctic climate change, the region and its people are being hit much harder and faster than the rest of the globe. Slow-moving decision-making and talk without follow-through will seriously endanger Arctic residents.

“I left the COP having a very hard time feeling ‘optimistic’, while knowing that the hazards of climate change are already severely impacting Arctic lands, cultural resources, food and water security, infrastructure, homes, and ways of living,” said Dr. Natali. “After repeated years of record-breaking Arctic wildfires, heatwaves, and ice loss, I’m not sure how a 1.5 or 2C warmer world—one in which we know that these events will only get worse—is a reasonable goal.”

Though missing necessary milestones at COP26, climate action is accelerating

Overall, however, the final Glasgow Climate Pact fell short of the ambitious action the world needs in order to limit warming. The deal made several last-minute compromises surrounding the phase out of fossil fuels. COP president Alok Sharma said that, while a future with only 1.5 degrees of warming is possible, it is fragile—dependent on countries keeping to their promises.

Despite this, McGlinchey says there was real progress at COP26. The conference reached a resolution that earned the unanimous agreement of all attending parties. The formal process has also begun to accelerate, with nations required to return with more ambitious climate mitigation plans next year, rather than on the previous five year timeline.

“We are not yet where we need to be,” McGlinchey said. “But we are better off than where we were two weeks ago. Let’s keep going.”

Imagining Earth’s most probable futures

New climate education initiative portrays the warmer worlds we are likely to see this century, in hopes of preventing them

One point five—most readers will recognize that number as the generally accepted upper limit of permissible climate warming. With current temperatures already hovering at 1.1 degrees Celsius above the historical average, the race is on to hit that target, and the likelihood that we will surpass it is growing. Even if we do manage a 1.5 degree future, that’s still warmer than today’s world, which is already seeing devastating climate impacts.

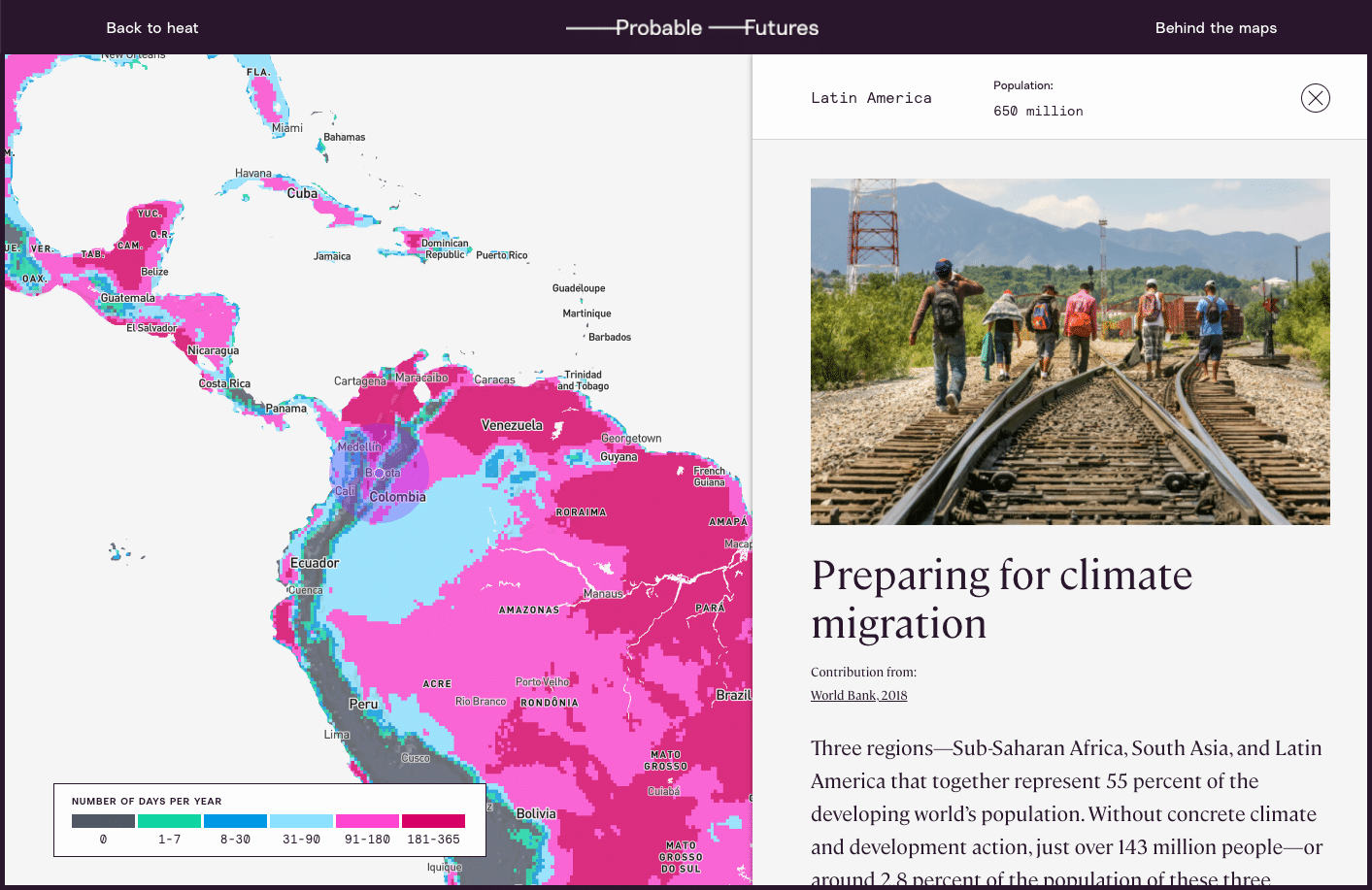

So what will it actually feel like to live in a 1.5 degree world—or a 2 degree one, or even 3? The Probable Futures initiative has built a tool to help everyone imagine.

Building a bridge between science and society

Probable Futures is a newly launched climate literacy initiative with the goal of reframing the way society thinks about climate change. The initiative was founded by Dr. Spencer Glendon, a senior fellow with Woodwell Climate who, after investigating climate change as Director of Research at Wellington Management, noticed a gap in need of bridging between climate scientists and, well… everyone else.

According to Dr. Glendon, although there was an abundance of available climate science, it wasn’t necessarily accessible to the people who needed to use it. The way scientists spoke about climate impacts didn’t connect with the way most businesses, governments, and communities thought about their operations. There was no easy way for individuals to pose questions of climate science and explore what the answers might mean for them.

In short, the public didn’t know what questions to ask and the technical world of climate modeling wasn’t really inviting audience participation. But it desperately needed to. Because tackling climate change requires everyone’s participation.

“The idea that climate change is somebody else’s job needs to go away,” Dr. Glendon says. “It isn’t anybody else’s job. It’s everybody’s job.”

So, working with scientists and communicators from Woodwell, Dr. Glendon devised Probable Futures—a website that would offer tools and resources to help the public understand climate change in a way that makes it meaningful to everybody. The site employs well-established models to map changing temperatures, precipitation levels, and drought through escalating potential warming scenarios. The data is coupled with accessible content on the fundamentals of climate science and examples of it playing out in today’s world.

According to the initiative’s Executive Director, Alison Smart, Probable Futures is designed to give individuals a gateway into climate science.

“No matter where one might be on their journey to understand climate change, we hope Probable Futures can serve as a trusted resource. This is where you can come to understand the big picture context and the physical limits of our planet, how those systems work, and how they will change as the planet warms,” Smart says.

Storytelling for the future

As the world awakens to the issue of climate change, there is a growing group of individuals who will need to better understand its impacts. Supply chain managers, for example, who are now tasked with figuring out how to get their companies to zero emissions. Or parents, trying to understand how to prepare their kids for the future. Probable Futures provides the tools and encouragement to help anyone ask good questions about climate science.

To that end, the site leans on storytelling that encourages visitors to imagine their lives in the context of a changing world. The maps display forecasts for 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 degrees of warming—our most probable futures, with nearly 3 degrees likely by the end of the century on our current trajectory. For the warming we have already surpassed, place-based stories of vulnerable human systems, threatened infrastructure, and disruptions to the natural world, give some sense of the impacts society is already feeling.

According to Isabelle Runde, a Research Assistant with Woodwell’s Risk Program who helped develop the maps and data visualizations for the Probable Futures site, encouraging imagination is what sets the initiative apart from other forms of climate communication.

“The imagination piece has been missing in communication between the scientific community and the broader public,” Runde says. “Probable Futures provides the framework for people to learn about climate change and enter that place [of imagination], while making it more personal.”

Glendon believes that good storytelling in science communication can have the same kind of impact as well-imagined speculative fiction, which has a history of providing glimpses of the future for society to react against. Glendon uses the example of George Orwell who, by imagining unsettling yet possible worlds, influenced debates around policy and culture for decades. The same could be true for climate communication.

“I’m not sure we need more science fiction about other worlds,” Glendon says. “We need fiction about the future of this world. We need an imaginative application of what we know.” Glendon hopes that the factual information on Probable Futures will spark speculative imaginings that could help push society away from a future we don’t want to see.

For Smart, imagining the future doesn’t mean only painting a picture of how the world could change for the worse. It can also mean sketching out the ways in which humans will react to and shape our new surroundings for the better.

“We acknowledge that there are constraints to how we can live on this planet, and imagining how we live within those constraints can be a really exciting thing,” Smart says. “We may find more community in those worlds. We may find less consumption but more satisfaction in those worlds. We may find more connection to human beings on the other side of the planet. And that’s what makes me the most hopeful.”

‘Summer of extremes’ briefing helps meteorologists connect extreme weather events to climate change

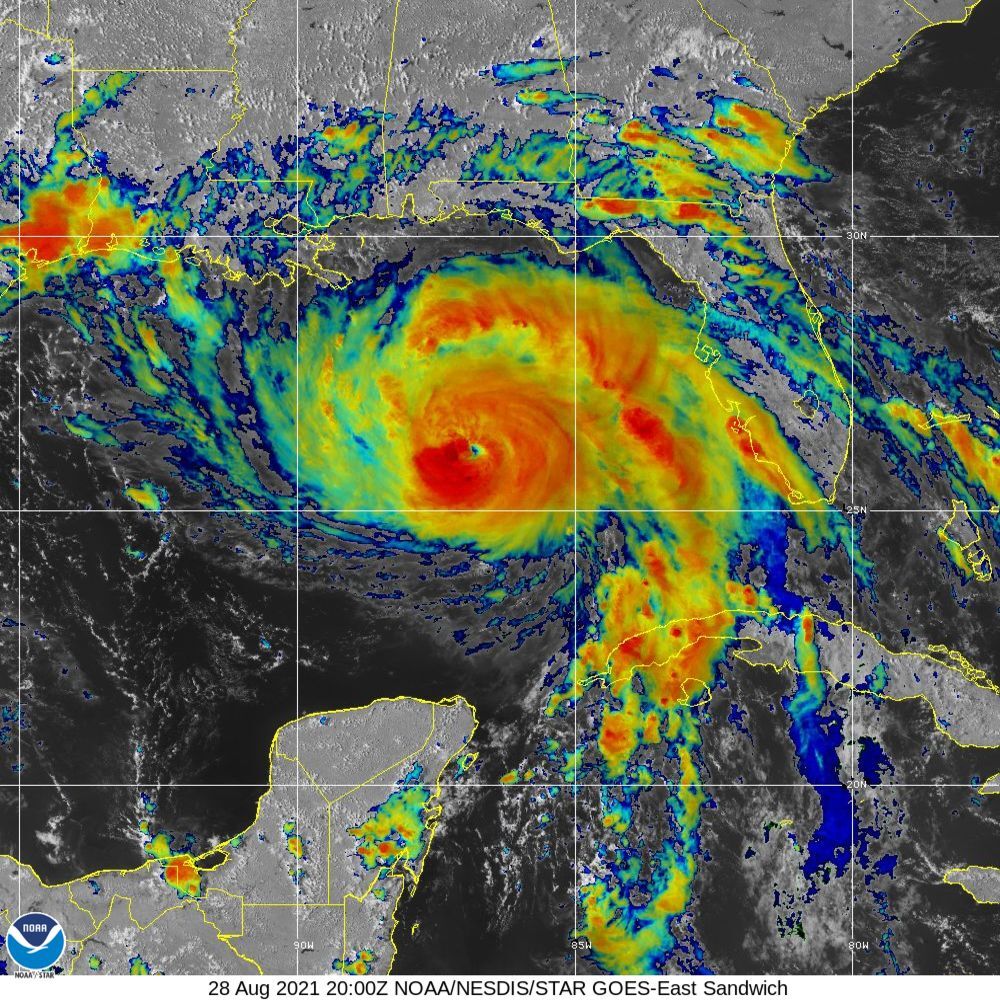

The summer of 2021 has been a summer of extremes. Catastrophic wildfires, drought, flooding and deadly heat waves are all signals of a warming climate, but the nature of that connection is often not well understood by the public. To help deepen understanding of the links between extreme weather and climate change, Woodwell hosted a briefing last week for a group that is always thinking about the weather: meteorologists.

The briefing was led by meteorologist Chris Gloninger of KCCI 8 Des Moines, who moderated a Q&A with Woodwell senior scientist Dr. Jennifer Francis and Assistant Scientist Dr. Zach Zobel. Dr. Francis and Dr. Zobel provided attendees with insight into how weather events, like the recent hurricanes Henri and Ida or flash flooding in Tennessee for example, are exacerbated by climate change.

Meteorologists, tasked with preparing local communities for changes in the weather, are uniquely positioned to communicate the role of climate change in weather patterns to a broad public audience. According to Dr. Francis, meteorologists are “often the only scientists that people come into contact with.” Which means they have a valuable opportunity to shape people’s perception of weather events as a consequence of climate change.

For Dr. Zobel, a meteorologist by training himself, one of the best ways to make those connections is by highlighting the specific elements of extreme events that the science shows are clearly linked to warming.

“Rather than focus on the storm itself, focusing on the features within the storm that climate models and observations show are clearly going to increase,” Dr. Zobel said. He cited the all time record for the amount of rainfall in one hour in New York that was broken during Henri. Heavy bursts of precipitation are likely to become more common with climate change, as a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor.

Meteorologists joined the briefing from across the United States, and were interested in the best ways to communicate climate science across diverse audiences, some of which might not be familiar with or accepting of climate science. Dr. Francis used the example of farmers in the Midwest who have reported more persistent weather conditions—longer droughts or storms—affecting their crops.

“If we can take that and link it back to how we think climate change is starting to cause more persistent weather patterns, that is something we can talk to them about that is really affecting how they do their business, how they live their lives, and is certainly something they are seeing every day,” Dr. Francis said.

Dr. Zobel also emphasized the need to communicate climate change in terms of personalized, individual impacts.

“Until we are able to do that, climate change may seem like a distant, far away problem,” Dr. Zobel said. “Once people see it’s affecting them locally they tend to re-evaluate.”

a