Indigenous territories protect Amazon carbon, but aren’t immune to degradation and disturbance

A new study suggests that Amazon Indigenous territories and protected natural areas are emitting formerly undetected amounts of carbon, yet their net emissions remain low, allowing them to outperform other land categories across the nine-nation region. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, was produced by scientists, policy experts, and indigenous leaders from Woodwell Climate Research Center (formerly Woods Hole Research Center), IPAM Amazônia, Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica (COICA), Rede Amazônica de Informação Socioambiental (RAISG), and Environmental Defense Fund (EDF).

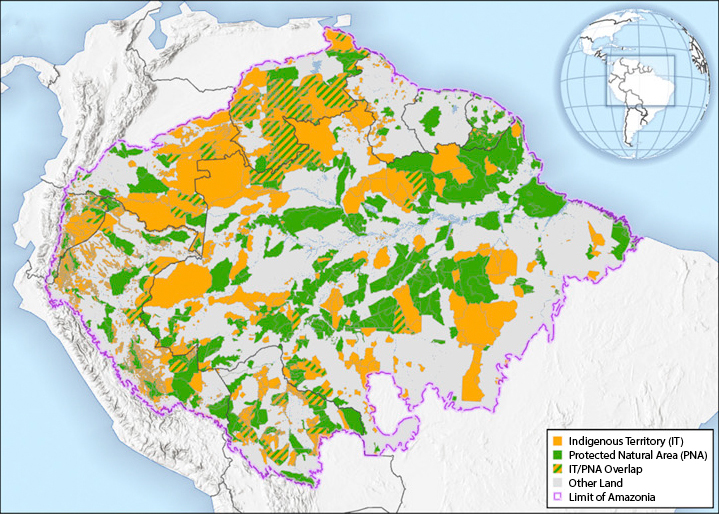

Researchers used innovative techniques to measure carbon emissions caused by forest degradation and disturbance, rather than deforestation alone, finding that forest growth helped indigenous territories show the lowest net loss of carbon, with 90% of net emissions coming from outside protected lands. Combined, Amazon indigenous lands and protected natural areas cover 52% of the Amazon and store 58% of its aboveground carbon.

Map of Amazonian land tenure. (Wayne S. Walker et al. PNAS 2020; 117:6:3015-3025)

The study suggests protected lands are increasingly at risk from illegal activities and growing threats to the rule of law, endangering their role in maintaining vulnerable landscapes intact. Their findings led the authors to call for strengthening the rights of indigenous peoples.

“The role that indigenous peoples and local communities have played in maintaining Amazon forests intact is indisputable, yet our study shows that their territories are not immune to forest loss from degradation and disturbance. That includes climate change, logging, mining, road-building, and other forms of development that act to diminish forest integrity,” said Woodwell scientist Dr. Wayne Walker, the study’s lead author.

The authors looked at losses and gains in carbon over the period 2003-2016, using an update to data originally published by a team that included Woodwell scientists Drs. Alessandro Baccini, Richard Houghton and Walker. Additionally, they disaggregated losses into those attributable to forest conversion (e.g., deforestation) and those due to anthropogenic degradation and natural disturbance.

Lands outside Indigenous territories and protected natural areas accounted for about 70% of total carbon losses and nearly 90% of the net change—on less than half the total land area. In contrast, Indigenous territories and protected natural areas comprise more than half the land area and contributed just 10 percent of the net change, with 86% of losses on those lands offset by gains through forest growth. Thus, there was a nine-fold difference in net carbon loss outside Indigenous territories and protected natural areas (−1,160 metric tons of carbon) compared with inside (−130 MtC).

Almost 90% of Amazon indigenous territories have some form of legal recognition, but the authors of the study note that government concessions for mining and petroleum extraction overlap nearly one-quarter of all recognized territorial lands, substantially increasing their vulnerability to adverse impacts.

“Our research reveals what indigenous peoples across the Amazon are reporting to their leaders,” said Tuntiak Katan, an author and vice-coordinator of COICA. “Governments are weakening environmental protections, violating existing indigenous land rights, and encouraging impunity in the rule of law. The situation is putting at risk the existence of our peoples and our territories, which contain the world’s most carbon-dense forests.”