Increasing soy and maize production grows into low-suitability land

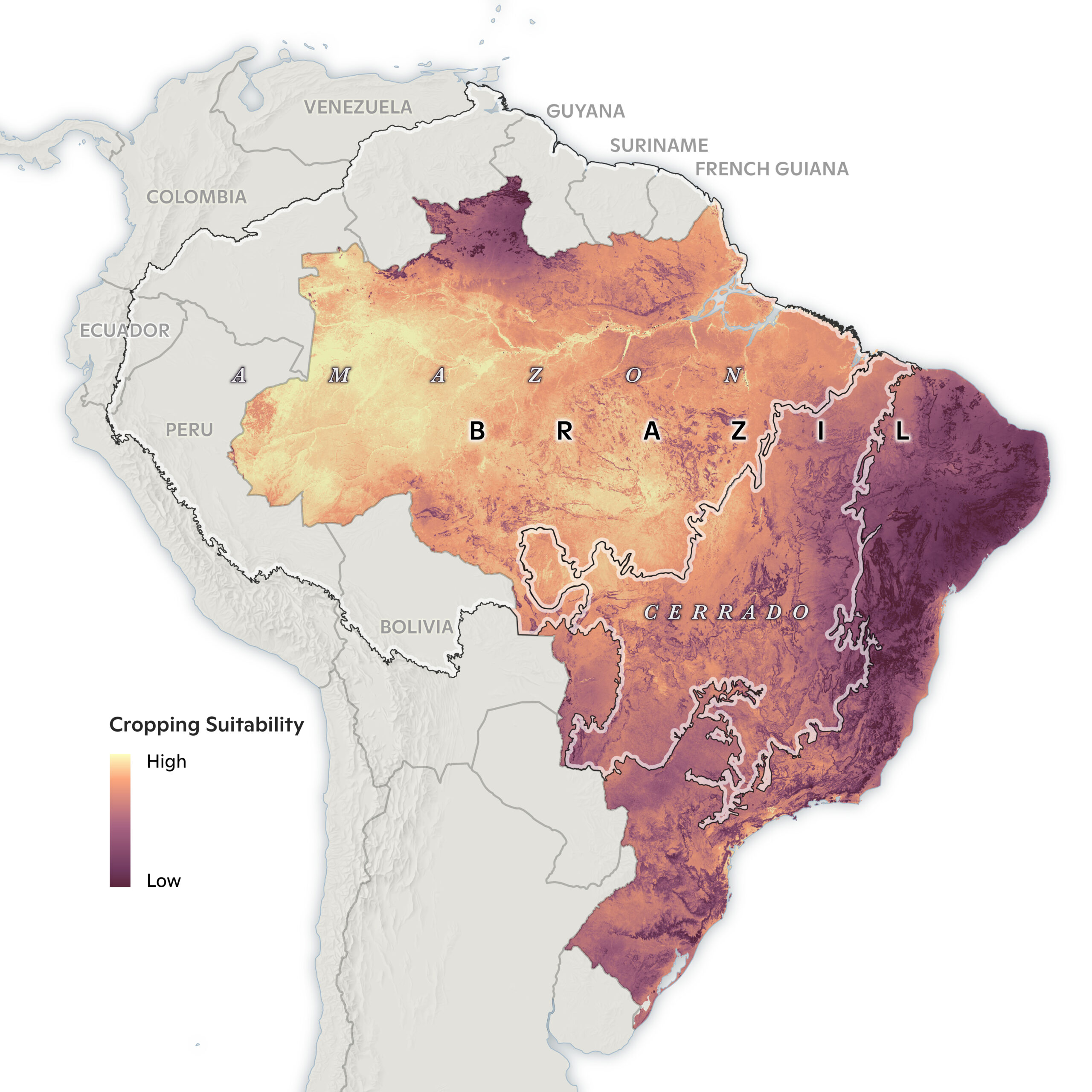

This study maps the most suitable lands for grain-cropping in Brazil. Agriculture is expanding beyond them.

Harvesting trucks on Tanguro ranch in Brazil.

photo by Nolan Kitts

A recent paper, led by Woodwell Climate postdoctoral researcher Dr. José Safanelli, revealed that Brazil’s farms have been steadily moving out of the most suitable regions for agriculture—opening up a significant portion of the world’s agricultural production to vulnerability from the changing climate.

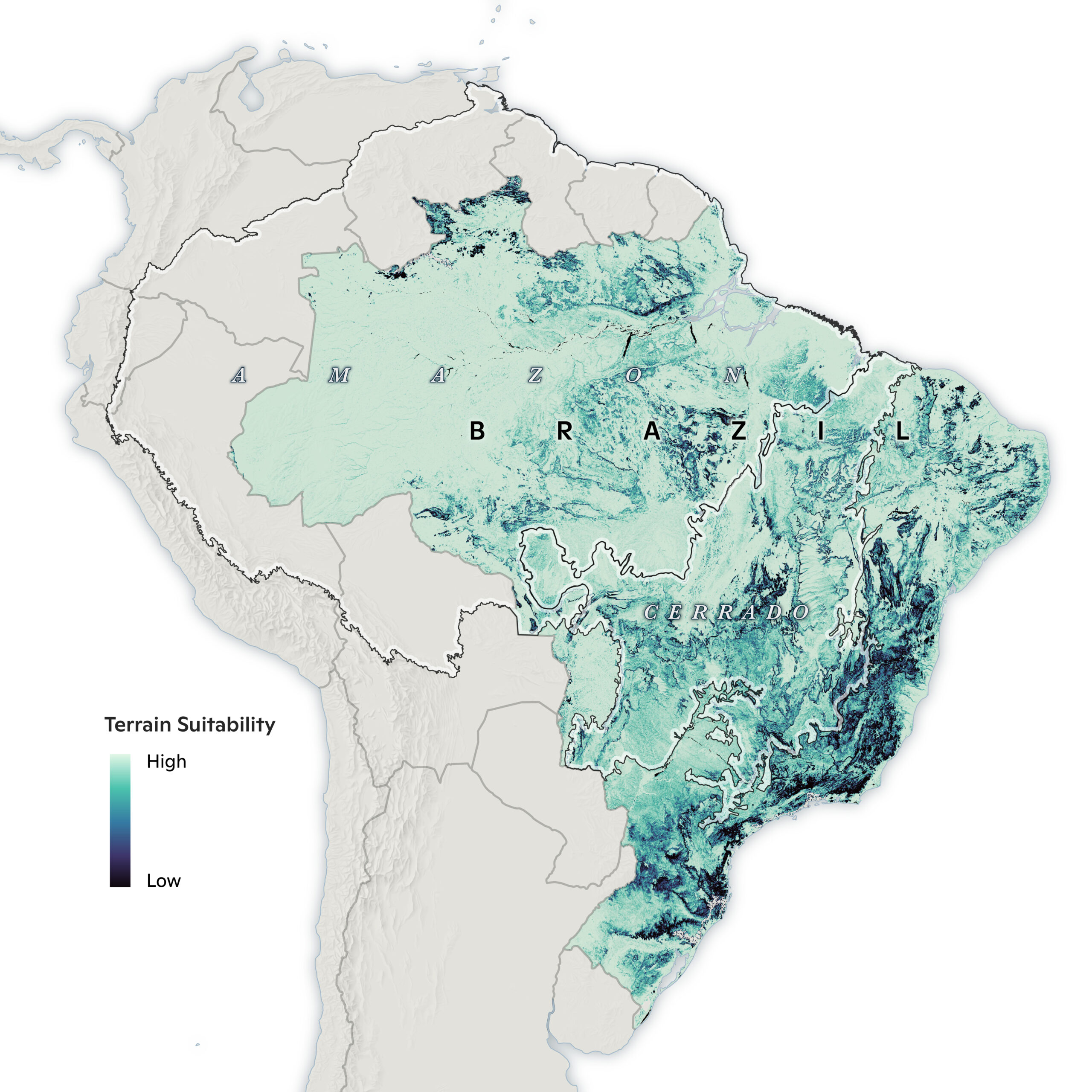

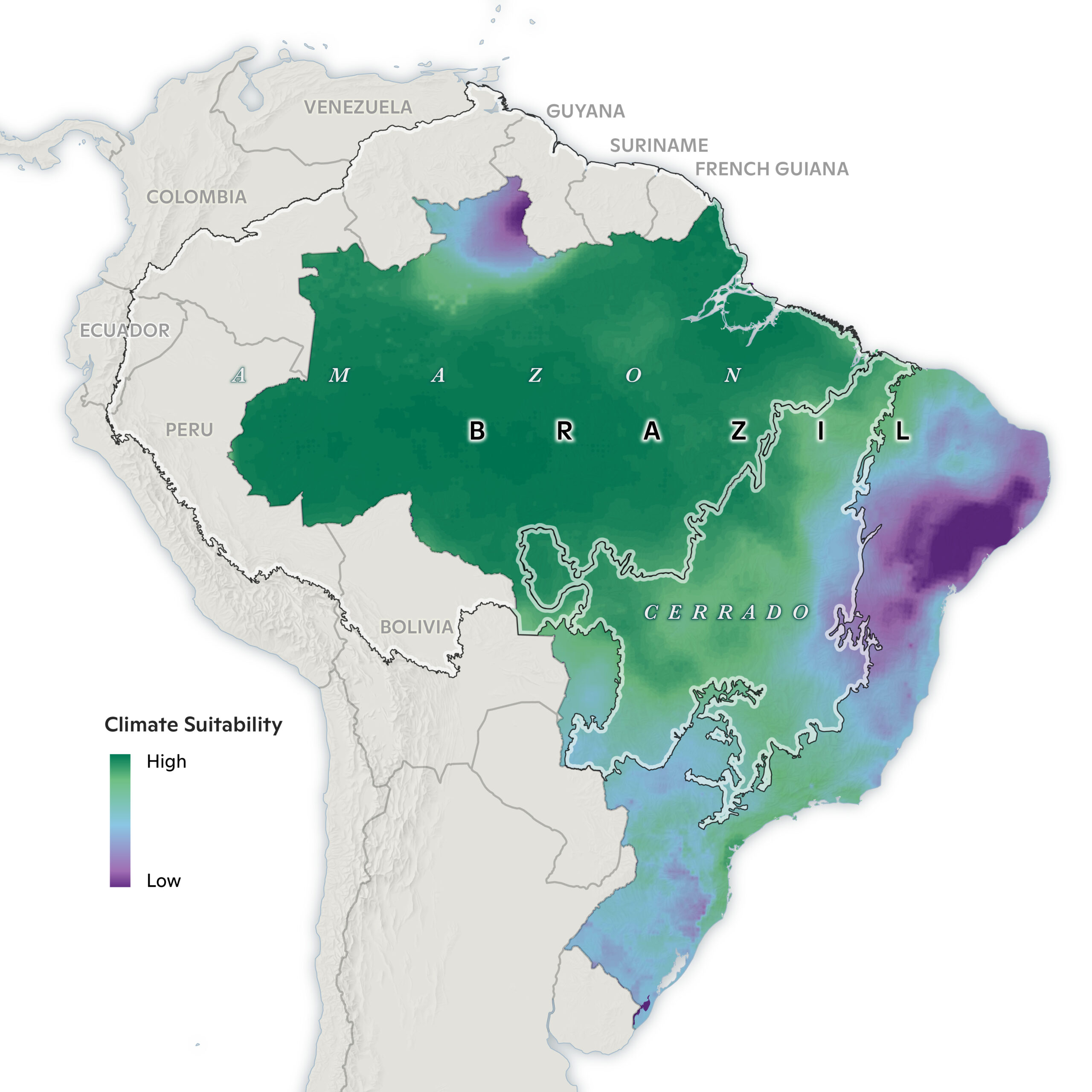

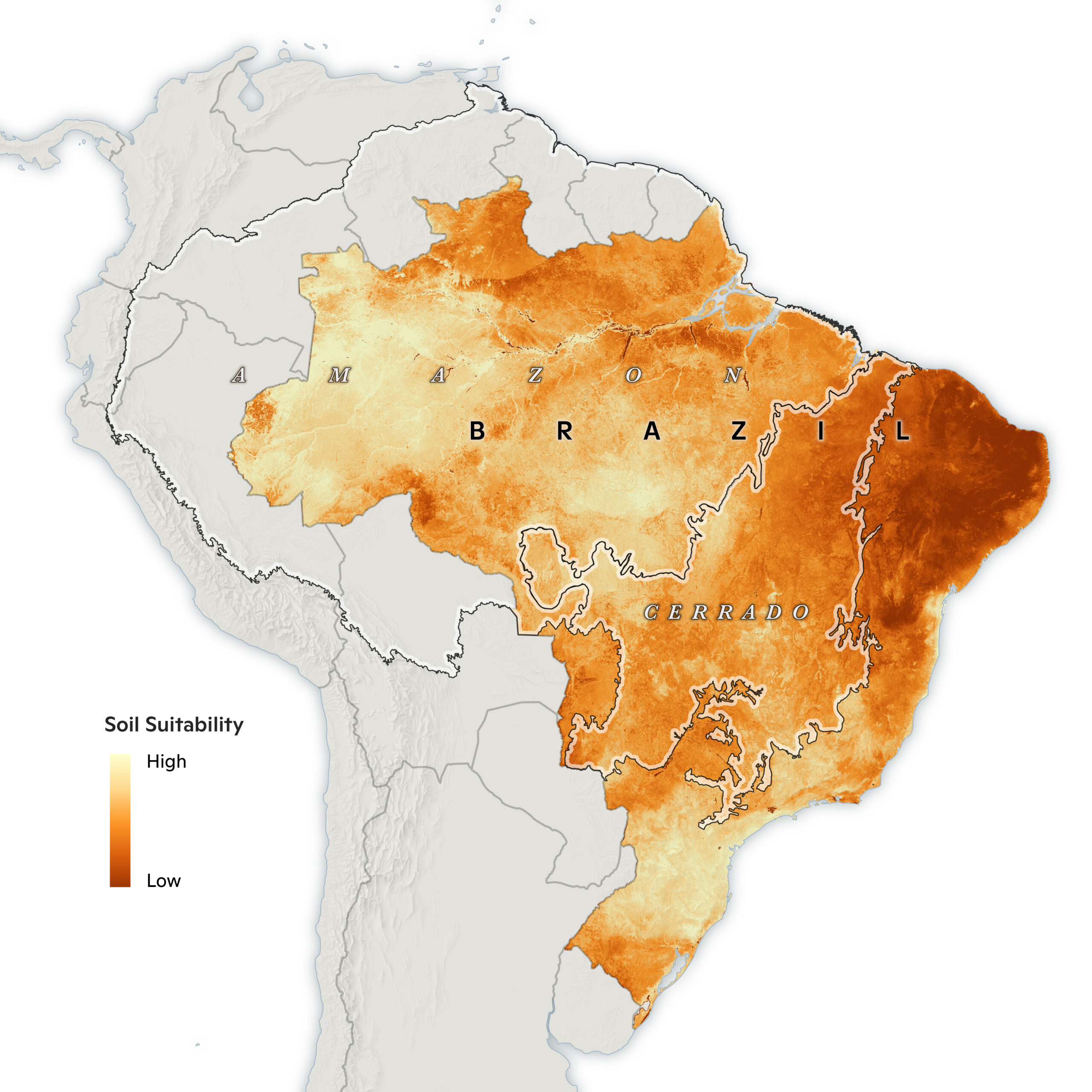

The study, published in Applied Geography, used an index to assess “Grain-cropping suitability” for two key staple crops—soy and maize. Suitability was determined by climatic factors (temperature and precipitation), as well as soil quality and terrain. The result was a continuous map detailing the areas of the country with the best biophysical conditions for growing crops.

Overlaying land use change data from the past two decades with this new map revealed a historical trend of agricultural lands expanding towards areas with poorer soil quality and lower suitability for grain-cropping, primarily in the north central and northeastern portion of the country.

maps by Christina Shintani

maps by Christina Shintani

For migrating farmers, terrain has been the most important factor in cropland expansion…

… followed by climate, and then soil quality.

Farmland expansion has typically neglected soil suitability in favor of better climate and terrain conditions.

This has introduced risk into the system, making food security more fragile.

Understanding Brazil’s agricultural migration

Farmers in Brazil have been moving north to this “agricultural frontier” since the 1980s—drawn primarily by economic opportunity, as well as the higher quality climate and terrain conditions along the southern edge of the Amazon.

Despite the favorable climate, the soil is inferior. Farmers are seeking cheap land, which often comes in the form of degraded pasture, originally created by clearing forest. Rainforest soils are not naturally nutrient rich and, without any additional inputs, the soil quality becomes depleted after just a few years. Many farmers know this fact, but come anyway. Dr. Safanelli has even seen this trend unfold within his own family.

“I was born in the south of Brazil, a region that has good soil conditions. Recently, two of my uncles who are farmers emigrated to Mato Grosso. There, the climate is wetter and more stable, but the soils are poor—depleted of nutrients.”

Additional research by Woodwell Climate Assistant Scientist Dr. Ludmila Rattis suggests that climatic advantage may be short-lived. Her work indicates that the climate in these areas is changing— becoming drier and hotter as global temperatures rise—and deforestation for agricultural expansion just makes the problem worse.

“We showed in our paper that these places have good climate and terrain suitability for now,” says Dr. Safanelli. “But they are restricted in soil quality. In Mato Grosso—the largest agricultural production state in Brazil—for example, the climate has been more stable and favorable than in other parts. The problem is that, according to projected climate scenarios, climate change may push these areas out of a good suitability space.”

What this means for agriculture in Brazil

Brazil is currently the world’s top producer of soy, and in the top three for maize. But this expansion into lower-suitability regions has introduced greater vulnerability into the agricultural system. Farmers already must provide greater investment in fertilizing the soil to make it productive, which cuts into their margins for profit. Add to that the fact that poor-quality soils, typically low in organic matter, can make crops less resilient to extreme heat and drought.

“Crop evapotranspiration—a process that directly governs crop growth and yield—depends on soil for absorbing rainfall and storing water. These marginal soils can make farmers more susceptible to climate change’s expected drier and warmer conditions, as they have limited capacity for storing water,” says Dr. Safanelli.

Reducing these vulnerabilities, Dr. Safanelli says, will require an integrated approach— improving land management practices and increasing crop yields on existing land to reduce the pressure to expand. “Reducing the vulnerability of croplands may be possible by adopting management practices that increase the resilience of the farming system, such as fully incorporating the principles of conservation agriculture, integrated production through agroforestry, crop-forest-livestock systems, or irrigation to control dryness. And perhaps allocating some of these marginal lands for land restoration, concentrating our resources in more highly suitable croplands.”