Recognizing risk—raising climate ambition

To make good decisions about responding to climate change, it is crucial that we understand the full scale of the risk.

Read and download the full report.

Introduction

The 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) brought countries together to accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). To date, however, progress with both national climate change mitigation policy and sub-national adaptation strategy have not matched the severe risks of impending climate change impacts, implying that climate risks are not being communicated and received effectively.

Currently, many climate risk assessments focus on a single hazard, cover large spatial and temporal scales, and often only look at global and national impacts through the end of the century. Climate risks are frequently shown as a function of various future emissions scenarios, which can be a source of confusion and uncertainty. There is still an enormous gap between our understanding of climate risk and climate policy ambition.

In this context, the COP26 Presidency and Woodwell Climate Research Center (“Woodwell”) organized country-specific workshops to understand how to better deliver climate risk information. We gathered high-emitting nations (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, South Africa, United States, and Turkey); collectively, these nations comprise approximately 67% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. We convened more than 220 cross-sectoral experts in climate policy, science, resilience, and advocacy, as well as those working in financial risk, to discuss both general perceptions of climate risks and specific aspects of climate risk assessments. Following these workshops, the conversations were distilled to identify the themes that emerged across all workshops, and those that were unique to individual countries. Our goals were to identify both the aspects of climate risk assessments that are most effective at motivating action and those that could be improved. With this report, we address both scientists who have traditionally been involved in the climate risk assessment process, and experts, stakeholders, and decision makers who for the most part, have not.

To produce these findings, Woodwell researchers synthesized detailed notes from each workshop to identify common themes, challenges, and suggested solutions. The document aims to deliver insight to the scientific community about how climate risk assessments for policymakers can be designed and delivered more effectively.

The best received climate risk assessments are the ones that deliver data at the scale that people work at.Workshop Participant, Australia

Cross-Cutting Opportunities and Challenges for Improvement

In this section we identify key findings that resonated across the workshops, and provide recommendations on how to address the most significant challenges.

Develop risk assessments in collaboration with policymakers

Climate risk assessments are most effective when they answer a specific policy question, and when they respond to an engaged audience eager to make use of relevant climate science. Most workshop participants indicated that for risk assessments to be successful and influential, they should be developed in partnership with policymakers.

For adaptation and resilience purposes, co-created risk assessments were cited as being effective in assisting implementation because they are designed with a specific set of climate hazards and the end user in mind. Collaborative climate risk assessment development requires shared understanding, strong relationships, and open channels of communication between scientists and policymakers. A recurring theme in the workshops was that scientists are not necessarily the best suited to communicate their results to non-technical audiences, and so in some cases, this might require an intermediary. Similarly, a number of workshop participants suggested that the most prominent climate risk reports—such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Reports—do not resonate far beyond academia because they do not use language that is accessible to non-scientists.

The benefits of scoping risk assessments in partnership with policymakers also extended to increasing ambition for mitigation policy as well. In countries where climate change has become a politically difficult issue, customized climate risk assessments were seen as a potential mechanism for spurring political leaders toward climate action. If a policymaker is particularly interested in agriculture, for example, a focused look at future crop yields makes the climate message more likely to resonate.

In countries where climate change policy is not a priority, focused climate risk assessments could bring much needed attention to the issue. In one country, workshop participants said that natural disasters are a significant problem but they are not often discussed within the context of climate change. For example, clearly attributing specific precipitation and flooding events to climate change—and explaining how they will become more severe in the future—would directly respond to an issue that policymakers feel compelled to prioritize.

“Scientists need to get feedback from the decision makers on what type of information they need and how they will use it,” said one participant in the China workshop. There is a “feeling that there is a significant gap between knowledge and action. Science is irrelevant if the governments don’t know how to use the scientific information correctly.”

RECOMMENDATION

Create channels for climate scientists to collaborate with policymakers, and support open and regular communication between these groups to build a shared knowledge base and appropriately address relevant policy questions.

Provide context-specific climate risk information

Risk assessments that provide detailed information about climate change impacts to specific communities are more likely to motivate increased mitigation efforts. While downscaled and locally-relevant risk assessments most often inform adaptation efforts, they also drive mitigation by increasing awareness of how climate change can destroy valued ways of life, and by demarcating the clear limits to adaptation and the potential loss and damage. Workshop participants agreed that local-scale assessments are important for the general population by allowing communities to see how climate change will affect their livelihoods and lives, and also for the political leaders who are responsive to those constituents and economic interests.

The types of specific risk information needed across societies are as varied as the communities themselves. One workshop participant reported that they had conducted 46 climate change meetings across the country, and through that process identified thousands of different assessment needs. For example, a sheep farmer in one of those meetings was reportedly interested in the changes in temperature at a certain height off the ground because of the implications for livestock breeding. While that level of modeling is not currently achievable, it speaks to the need for context-specific information.

To provide this information, workshop participants encouraged the use of climate risk modeling that produced higher resolution spatial data over shorter timescales. This would be applicable and useful on both regional and municipal levels. While multiple workshops focused on the need for a more standardized and uniform set of scenarios under which risk can be assessed, the need for customized and locally relevant outputs stood out.

RECOMMENDATION

To illustrate localized risk that can be avoided and to highlight the limits to adaptation, stakeholders should be continually engaged in regional climate modeling and climate model downscaling.

Standardize climate risk assessments

Many of the workshops cited the need for a standardized approach to climate risk assessment, which would allow senior policymakers and business leaders to make comparisons across geographies and sectors.

Scientists should “build on current assessments and develop a more standardized and uniform set of scenarios under which risk can be assessed at different scales so people don’t have to sift through a lot of different reports,” said a participant in the Australian workshop.

The discussions touched on the benefits of standardized climate risk assessments to political leaders, but also emphasized the specific help this would provide to understanding the financial cost of climate change impacts.

Banking officials “are beginning to factor climate-related risks into regulation, but it is difficult without any international consensus on how to do this,” said one Russian participant.

RECOMMENDATION

Best practices should be standardized in climate assessment processes to facilitate comparisons, while ensuring that each assessment is tailored to a specific audience.

Engage interdisciplinary teams to illustrate cascading climate change impacts and develop solutions

Climate risk assessments that go beyond direct physical hazards are more likely to resonate with political leaders. Every workshop session agreed that physical climate risk assessments are more compelling when they are translated into socio-economic metrics such as public health, jobs, and economic productivity. Public health assessments, in particular, were identified as being important for both adaptation planning and for catalyzing increased climate policy ambition. Regardless of the application, in order to translate climate hazards into climate impacts, vulnerability assessments must be incorporated into the climate risk assessment process.

“We need to explain climate change using examples of what people are dealing with on a daily basis,” said one South African participant. “Climate change language easily becomes too scientific… once everyone can have a conversation and understanding of climate change, it will spur mitigation and adaptation efforts across sectors.”

Many of the workshops also placed particular emphasis on the need to quantify the costs of climate change impacts, such as the future economic cost of climate change for agricultural production. For example, one workshop noted that shifting climate zones might require the relocation of entire sectors of the country’s agricultural sector—at a potentially enormous cost. Some participants also suggested that risk assessments could often do a better job of identifying compound and cascading risks, to fully illustrate the potentially calamitous scale of the climate crisis. In that vein, workshop participants repeatedly mentioned that calamitous climate risk information presented by itself can be overwhelming and off-putting. In order to prompt action, clear solutions need to be put forward, further highlighting the need for interdisciplinary collaboration so that appropriate next steps can be developed to accompany climate risk assessments.

RECOMMENDATION

Support interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral teams to co-create climate risk assessments and complementary solutions that will sufficiently address cascading climate impacts.

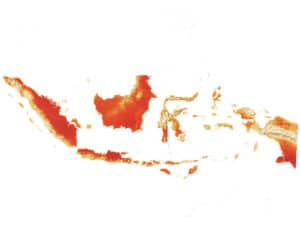

According to workshop participants, the Indonesian government is committed to spending money on climate change mitigation, but many Indonesians within government and in the general public still do not appreciate the severity of the threat. Participants said that the IPCC assessments reports—for example—were often ineffective because there was no framework to explain the relevance to Indonesia at national or subnational levels. As with several other workshops, the group emphasized the need for geographically relevant risk assessments that are paired with solutions.

In those communications, participants encouraged more use of climate risk maps to demonstrate localized impacts, as well as close collaboration with communications experts to deliver the science effectively.

The workshop participants cited flooding, extreme heat, and agricultural impacts, as some of the most prominent climate-related concerns in Saudi Arabia. According to the workshop, major international climate risk assessments appear to be consumed primarily by academics, rather than by policymakers and the general public. Workshop participants noted that there is increased engagement between Saudi climate scientists and government officials, and climate change research was an area of growing focus within Saudi Arabian academic circles.

Like many of the workshops, participants agreed that improved communication among stakeholders is essential to gather necessary data. With the limited data available, the Russian Central Bank is completing climate stress tests to understand the risks and strategize low carbon options for Russia.

The workshop participants put forward several alternative approaches for using climate risk assessments to prompt more ambitious climate policy in Brazil. One potential path was through policy at the subnational government level, where political leaders seem more welcoming to climate science and risk assessments. Another path was through the private sector, focusing on finance and agriculture, as these two industries are highly exposed to climate risk. The consensus was that the private sector might respond to risk that is communicated in more detailed and explicit financial terms, as well as better communication of cascading climate change risks.

Participants emphasized that actionable information will look different to different groups, highlighting the need to work with local decision makers and stakeholders from the outset. The data collected, the analysis, and ultimately the messaging must be tailored to a particular audience. In that vein, the climate scientists who analyze the data are not necessarily the most qualified to deliver the message. Well-developed relationships between the communicators of climate risks and stakeholders are critical to successful delivery, according to participants. This workshop also highlighted the need to provide actionable solutions in tandem with climate risk assessments, to avoid worst-case

scenarios being delivered without context on pathways to avoid those outcomes. When developing solutions in response to climate risks, a multi-disciplinary approach is necessary because climate change intersects with a variety of other socioeconomic issues and stressors.

In line with other country workshops, participants advocated for climate risk communication that is closely tailored to the desired audience. For example, climate risk messages to decision makers should focus on solutions and be pragmatic; messages to local communities should be translated into the specific impacts that that community will face. On a national level, the workshop raised the possibility that large Indian corporations—which are acutely aware of their climate risk exposure—could take the lead on setting ambitious climate change policy.

The workshop addressed the need for international climate policy to address livelihood inequities—such as refrigeration, air conditioning, and transportation—between developed and developing countries when forming adaptation and mitigation strategies.

According to workshop participants, it will be useful to develop crop-specific climate risk models in order to assess how specific agricultural commodities will be influenced by climate change and to support effective adaptation strategies in farming communities.

Workshop participants also highlighted the need to quantify not only the future physical impacts of climate change, but also the economic costs these impacts will have on different agricultural commodities. This would not only serve the purpose of providing stronger evidence to motivate political action, but would also help develop processes to support adaptation in agricultural communities.

As with other country workshops, Canadian participants said that risk assessments that are tailored to specific policy concerns of government leaders may be more effective at raising policy ambitions.

The participants also said that effective risk assessments should not only lay out future hazards, but should also present tangible solutions, developed by cross-disciplinary teams of experts and stakeholders.

Workshop participants highlighted two specific impacts of climate change in South Korea. The first was the impact of heatwaves, particularly in urban areas and the related impacts on human health. The second was the indirect impact of climate change on agriculture and fisheries. Participants discussed the need for risk assessments to align with and inform adaptation plans, and the need to centralize both risk assessments and adaptation plans across multiple levels of government. As risk assessments and adaptation planning become more interwoven in the future, workshop participants said that stakeholders need to be involved in the assessment process by identifying existing data needs and gaps, and to ensure that vulnerable populations are not excluded from adaptation planning.

Several workshop participants also advocated for more positive communication in risk assessments. They suggested that communicating risk assessments alongside the success of previous policy initiatives and the opportunity, co-benefits, and economic stability of a net zero future in Australia may be the best way to encourage further action.

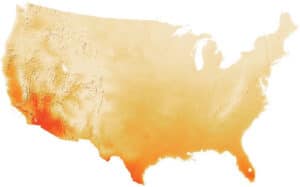

It is inadequate to help people understand risk, they need to know how to respond to the risk.Workshop Participant, United States

Conclusion

Rapidly improving climate modeling capability has illustrated climate change risks with greater clarity than ever before. Scientists are providing unprecedented insight into the threat of severe events, from sea level rise and flooding, to heat stress and wildfire. At the same time, national climate policies are woefully insufficient to mitigate the climate crisis. With the world on track for future warming of at least 1.5°C, national leaders must dramatically reduce global emissions in order to maintain hope of restoring a safe and stable climate. Current Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, however, still set a path for an increase in global emissions in 2030.

This disconnect between climate risk and current climate policy suggests that scientific assessments are not being internalized by national leaders in a way that prioritizes climate policy. The Recognizing Risk—Raising Climate Ambition workshops demonstrated the potential for climate risk assessments to be delivered more effectively to encourage greater policy ambition from senior policymakers.

The discussions identified challenges that were unique to specific countries. Some are solvable, such as a lack of available data. Others are more challenging, such as political leaders who are not open to receiving any form of climate science. In the face of national-level intransigence, the workshops discussed the potential for climate policy progress to be led instead by subnational governments or from large private sector entities who are acutely aware of their climate risk exposure.

Many of the workshop participants cited the need to combine risk assessment with more positive messaging, highlighting new opportunities and providing actionable solutions.

“Scientists should not act like doctors giving a terminal diagnosis,” said one participant in the US workshop. “We need to deliver the diagnosis with a cure.”

Ultimately, there were four key findings on how climate risk assessments could more effectively cut through to senior political leaders:

- Develop risk assessments in collaboration with policymakers

- Provide granular climate risk information about specific locations and industries

- Standardize best practices in climate risk assessments

- Engage interdisciplinary teams to illustrate cascading climate change impacts

Participants made clear that these solutions must come collectively from the scientists, policymakers at multiple levels of government, and stakeholders. They must, above all, be collaborative. But fully implemented, these steps could help make clear the scale of the climate crisis and the need for more urgent and more significant policy action.

Read and download the full report.