A warmer world means snow, rain will be much less predictable

Teenagers play soccer in the rain in São Paulo, Brazil.

Photo by Marlon Dias

When and where precipitation falls can determine whether or not people have enough drinking water, aquifers can support agriculture, and rivers keep running. Climate change is breaking down the predictability of weather patterns across the globe. Two new releases this week, from the Woodwell Climate Research Center and Probable Futures, flesh out our understanding of how the shifting seasonality of precipitation might impact our future.

Rainy seasons are fluctuating more

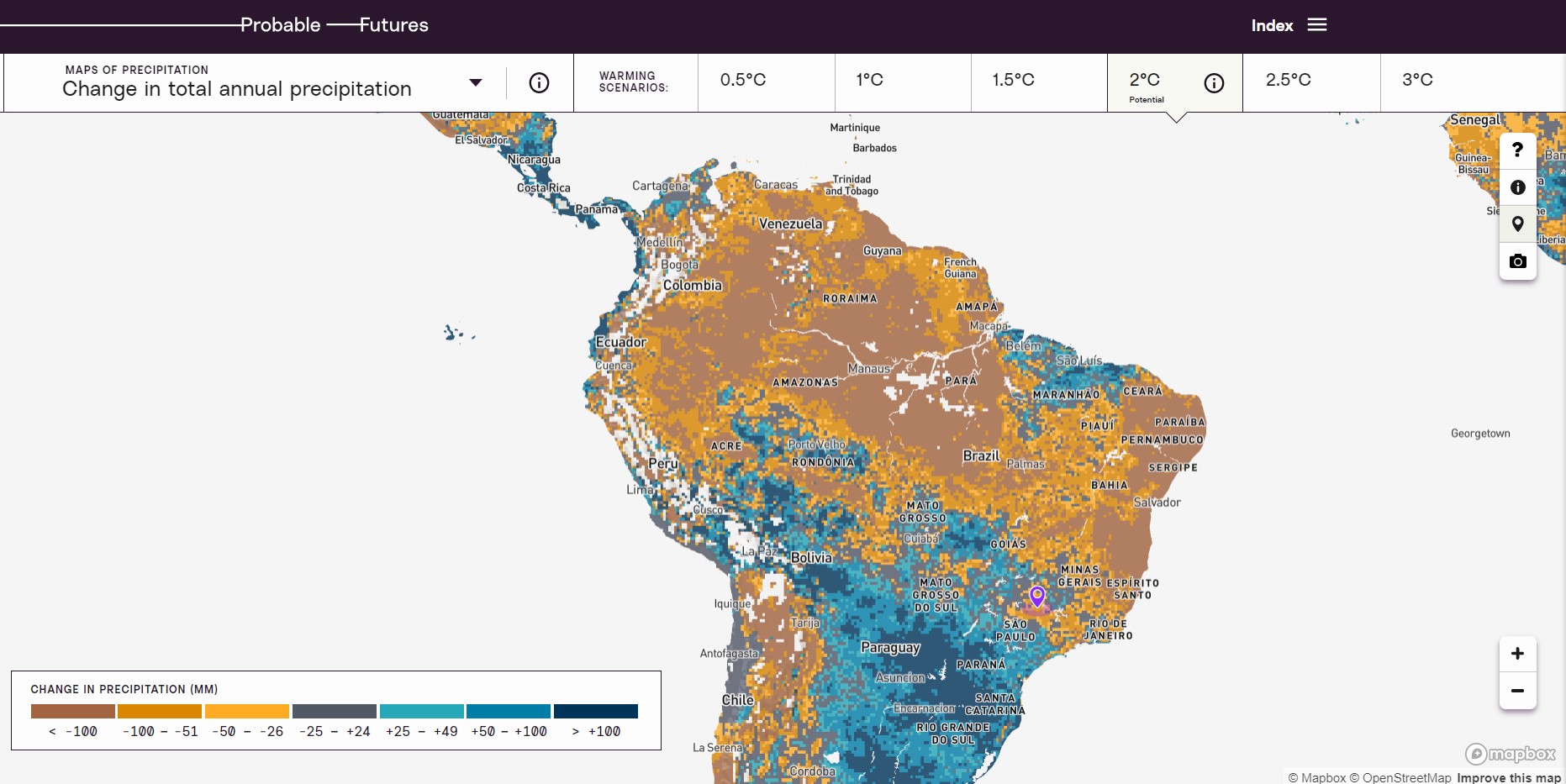

A new volume of maps, data, and educational materials launched on the Probable Futures platform today. The volume provides information that helps readers better understand local, regional, and global precipitation trends, showing how they will change with climate change.

The impact of a warmer world on precipitation patterns is not uniform—in some places dry spells will become more common, in others, intense storms, and some places will fluctuate between both. Rainy seasons may start earlier or later in different parts of the world, which will have impacts on growing seasons and agricultural yields.

Probable Futures platform shows the change in precipitation for Brazil predicted if the world warms 2 degrees celsius.

“Climate change is reshaping both local precipitation patterns and the global water system—and everyone on Earth will be affected,” said Alison Smart, executive director of Probable Futures. “It may seem counterintuitive, but knowing that the future is less predictable is a valuable forecast. Communities need to be more resilient, adaptable, and prepared. It’s within our power today to prepare for the events that are probable, and prevent those with irreversible impacts.”

Snow is melting earlier

Woodwell Associate Scientist, Dr. Anna Liljedahl and Assistant Scientist Dr. Jenny Watts, were co-authors on a paper also released today that documents the impacts of earlier snowmelt in the Arctic. The Arctic is warming more rapidly than anywhere else on earth, which has led to earlier snow melts and longer growing seasons in the tundra.

Conventional hypotheses have predicted that lengthening summers would allow more time for vegetation to grow and sequester carbon, perhaps offsetting emissions elsewhere.

“Our results show that the expected increased CO2 sequestration arising from Arctic warming and the associated increase in growing length may not materialize if tundra ecosystems are not able to continue capturing CO2 later in the season,” said Dr. Donatella Zona, lead author on the paper from the University of Sheffield’s School of Biosciences and the Department of Biology at San Diego State University.

Dr. Liljedahl says that the results highlight the fact that the impacts of climate change will be complex across ecosystems.

“This work shows how important it is to continually assess our assumptions and terminology on how the Arctic system will respond to warming. We often say that warming will lead to a “longer growing season”. We need to be more careful in making that connection,” said Dr. Liljedahl.