Think like an ecosystem

Two long-term research projects enter their third decade, bringing new insights into ecological change

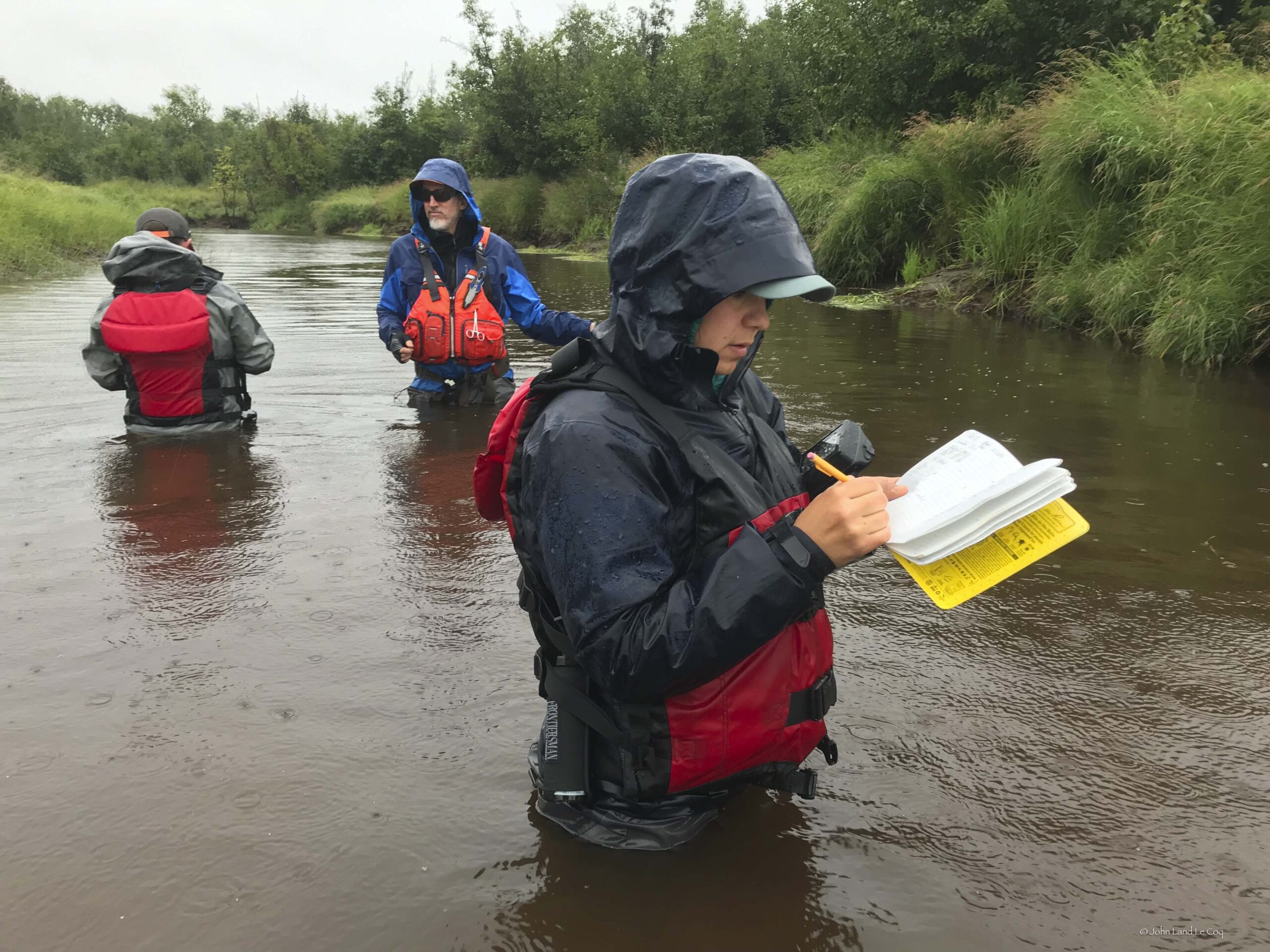

TIDE researchers take measurements in Plum Island Estuary.

photo by Hillary Sullivan

It didn’t matter that she didn’t speak any English at the time, or that the American researchers who had chartered her father’s boat that summer didn’t speak any Russian, 14 year-old Anya Suslova was a quick learner. She watched them dip sample bottles into the Lena River, filter the water, and mark information down on the side of the bottle. By the end of the two week research expedition, Suslova had mastered the protocol and was helping Dr. Max Holmes and his fellow scientists collect water samples.

When the scientists returned to the United States, they left behind some equipment, in case Suslova and her father were interested in sampling throughout the winter. After a year without contact with Suslova, the researchers were delighted to return to the Lena the following summer to find months of samples and a neatly organized logbook she made.

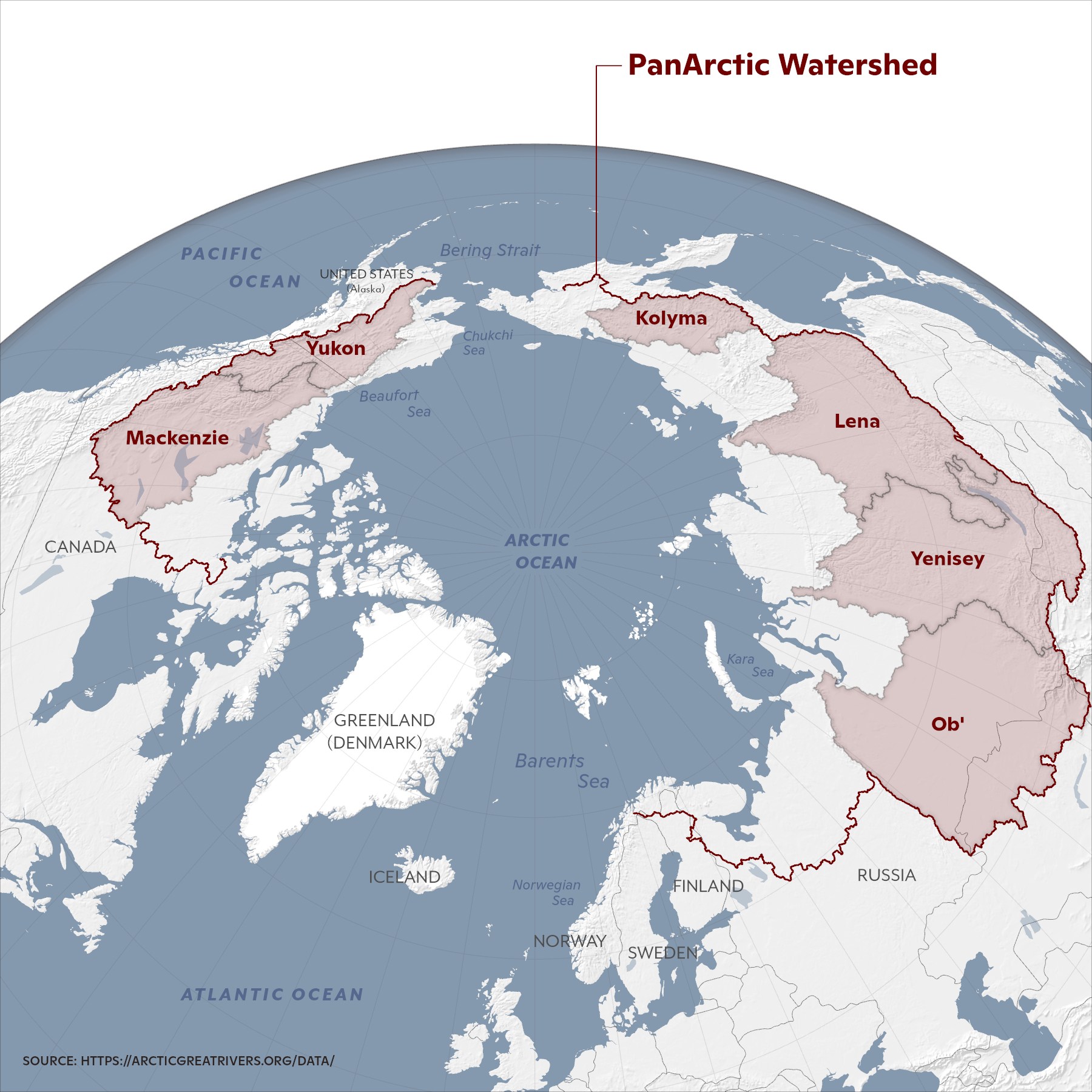

Twenty years later, Suslova is a Research Assistant at Woodwell Climate Research Center who continues to bring her expertise and unique perspective to the Arctic Great Rivers Observatory (ArcticGRO). Since 2003, participants of ArcticGRO—scientists and Arctic community members alike—have been sampling water from the six largest rivers in the Arctic: the Ob’, Yenisey, Lena, and Kolyma in Siberia, and the Yukon and Mackenzie in North America. It’s a rare example of a long-term research project, designed to span decades, deepening our understanding of change across the years.

Anya Suslova on an Arctic river research trip.

photo by John LeCoq

We need to establish baselines

The Arctic is warming, on average, at least two times faster than the rest of the planet. We need to know the implications of this, but it can be difficult to study ecosystem change across such a vast area. Rivers can offer insights. The chemistry of a river connects environmental processes across its watershed, and the dissolved and particulate materials that are carried to the ocean can influence marine chemistry and biology. Measuring the concentrations of these materials, and how they are transported by rivers, provides vital information about changes in the linkages between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

map by Greg Fiske

“Global climate change is rapidly and disproportionately affecting northern high latitude environments,” says Dr. Scott Zolkos, a Research Scientist at Woodwell Climate and one of ArcticGRO’s lead scientists. “Monitoring Arctic river chemistry is critical for detecting trends and understanding the effects of environmental change on northern ecosystems.”

In order to uncover those trends and effects, we need to establish baselines on the key chemical constituents within rivers—organic matter, inorganic nutrients like nitrogen, sediments—to compare against future measurements. The more data gathered, the easier it is to sift out annual variability from longer term trends.

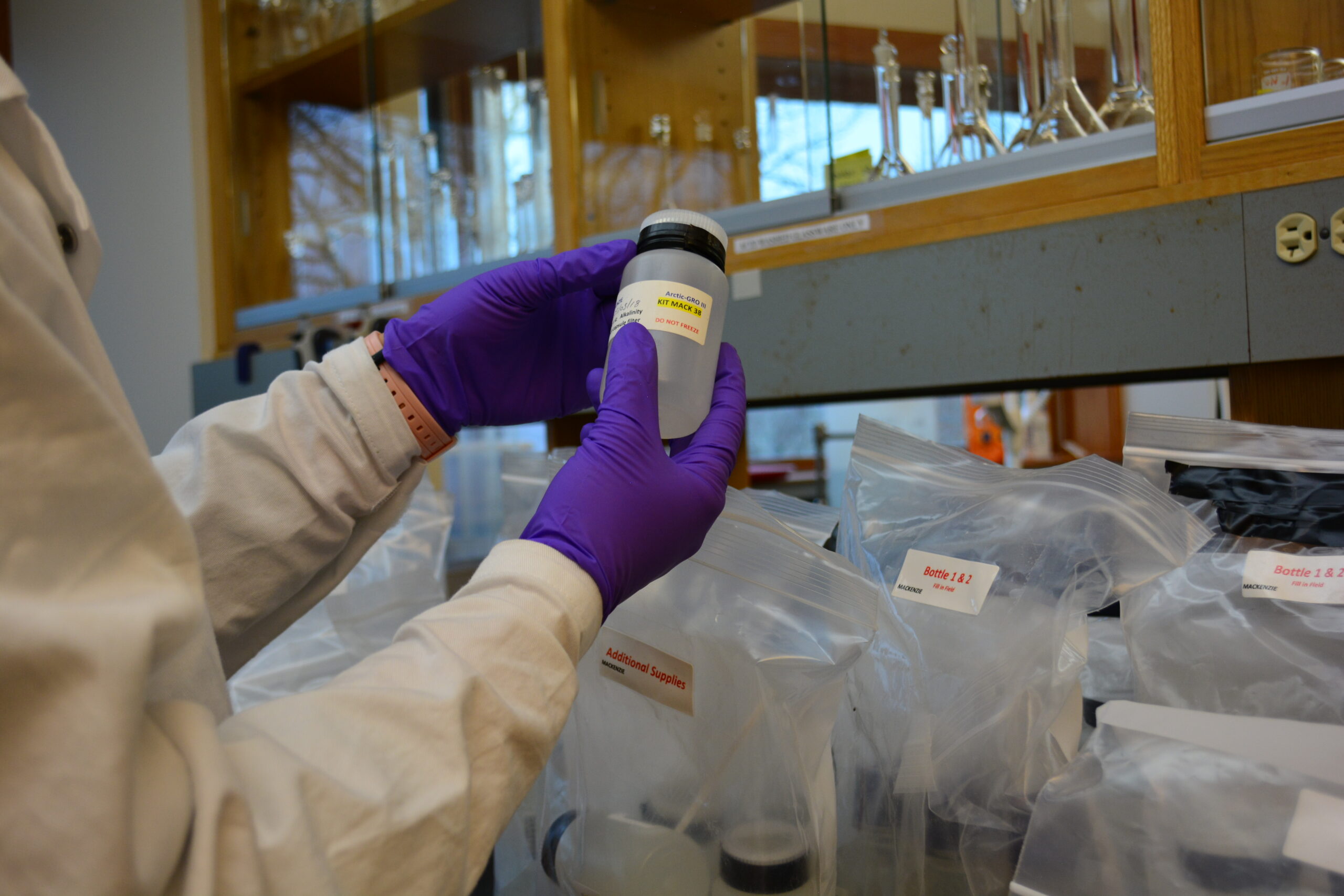

Suslova handles ArcticGRO sample bottles in the lab.

photo by Lindsay Scott

So, using Arctic rivers as sentinels of ecosystem health and environmental change was the idea behind the project’s creation, but it was the international collaboration that started with Suslova that gave ArcticGRO its longevity. The project leaders realized that enlisting the help of trained local residents could allow for sample collection in places, and during times of the year, that the researchers themselves couldn’t access. It also helped build enthusiasm for the project among Arctic communities.

“I believe that ArcticGRO has been able to go for so long because it is built on trust and a shared goal between scientists and local people who collect water samples,” says Suslova. “Amazingly the team of ArcticGRO hasn’t changed much over the last two decades, many of the original members are still involved. It feels like a family.”

Now, 20 years after its inception, the ArcticGRO team has published a paper in Nature Geoscience on long-term trends in pan-Arctic river chemistry. The team found strong signals of environmental change for some chemical constituents, but not in others. Alkalinity, which reflects rock weathering, increased in all rivers, while nitrate, an important nutrient for terrestrial and aquatic organisms, decreased. The authors hope the data and insights from this work will be invaluable to scientists refining models of the Arctic system.

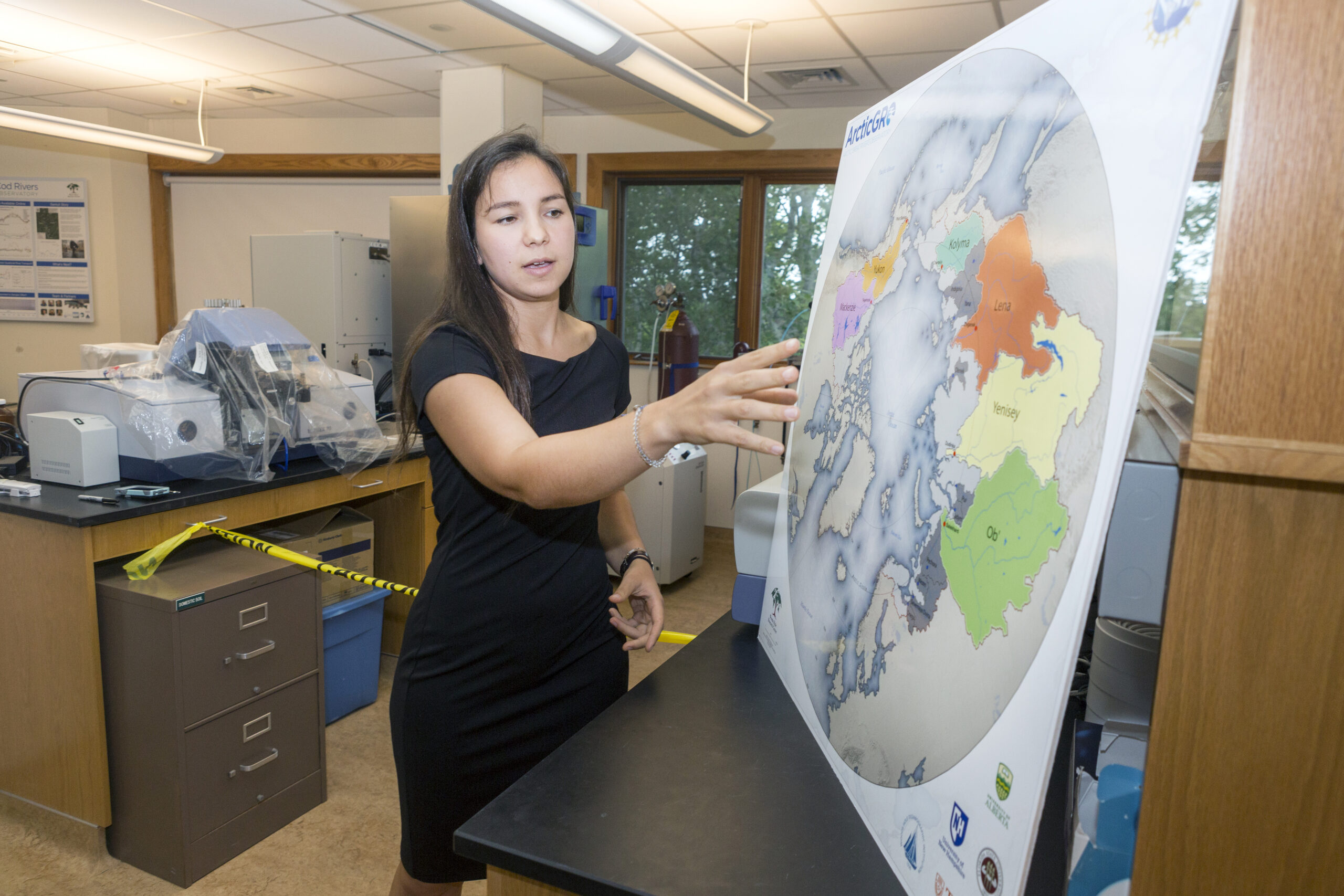

Anya Suslova presents the ArcticGRO project.

photo by Lauren Owens Lambert

“There’s nothing quite like ArcticGRO,” says Zolkos. “It’s unique in that it measures a comprehensive suite of chemical parameters across the Arctic’s largest rivers, uses consistent sampling and analytical methods across the rivers, and sampling occurs at the same times and locations. The consistency of ArcticGRO is increasingly valuable, because it is building a dataset which allows scientists around the world to detect, monitor, and understand northern environmental change in ways that no other scientific program does.”

We never would have known

A few thousand miles south of the Arctic circle, on the marshy coastline of Massachusetts, another long-term ecological research project has entered its third decade as well. The brainchild of Senior Scientist Dr. Linda Deegan, the TIDE project is unique even among long-term studies. Rather than simply monitoring the nutrient flows in the salt marshes of Plum Island Estuary, the TIDE project has been altering nutrients in carefully controlled amounts to understand the long term impacts of human development in coastal ecosystems.

TIDE focuses on nitrogen, an element of most fertilizers and a common pollutant from developed areas in the uplands. Previous studies of nitrogen impacts indicated coastal marsh plants could absorb a lot of nitrogen with no ill effects. But that dynamic was only examined on short time scales, and in small plots of marsh. Whether there were changes that might require many years or many acres to be detected, was unknown.

Thus TIDE was designed to increase nitrogen concentrations in the water to mimic coastal eutrophication across three marshes in the Plum Island estuary and document which effects might cascade through the system. The initial grant was for five years, but Dr. Deegan and her collaborators wanted to keep the project running for at least a decade, if not more, expecting the changes might be slow to reveal themselves.

After years of observations, Dr. Deegan says she remembers the exact moment they discovered a significant change.

“Several of the senior scientists—myself included—came back at the end of a long field day each of them saying, ‘I don’t remember it being this hard to walk through the nutrient enriched marsh when we started this project. Am I just getting older or has something changed?’ And then one of the new students said, ‘I thought that marsh was always like that—well, it’s not like that in the other sites where we haven’t added nitrogen.’”

So they followed the hunch, made some new measurements, and found the structure of the marsh had changed significantly with the added nitrogen. The plants, suddenly awash in a necessary component for growth, no longer needed to dedicate their energy to making roots to seek out nutrients; their root systems were shallower and less dense, thus less capable of holding the marsh together. At the same time, nitrogen-consuming microbes were breaking down organic matter in search of carbon to fuel the chemical processes that allow them to take up nitrogen. This combination made the marsh creek edges more susceptible to erosion by tides and storms.

It took more years than most experiments are run for, but increased susceptibility to erosion steadily altered the shape of stream channels. The ground along the edges of the streams, previously held in place by a deep network of roots, now collapsed underfoot. Chunks of marsh fell off the edges as the roots no longer held the marsh together. As the years went on, fish and other organisms that travel along stream floors to seek out food began to suffer from difficult terrain, resulting in slower growth and fewer fish.

These findings, published in Nature, upended the way people thought about the effects of eutrophication on marshes. “And we never would have known any of that,” says Dr. Deegan. “If we hadn’t done the project at an ecosystem scale and over such a long time.”

A pipe you can turn off

Over the decades, the TIDE project not only faced the challenges of running a consistent project for so long, but also of justifying making intentional changes to an otherwise healthy ecosystem. The question lingered: If the goal is to protect ecosystems from human disruption, what do we gain from knowingly tinkering with them?

Humans have already accidentally conducted thousands of ecological change experiments across the globe. Casually inflicted pollution, deforestation, or extinction with no control group, no careful observations, no time limits or safeguards—by scientific standards these are reckless and poorly designed experiments.

In Deegan’s mind, this makes controlled studies like TIDE even more significant.

“We need to know the true impact of the changes that we are already imposing on the environment. And once we do, we need to be able to halt those changes that threaten the integrity of an ecosystem.” Says Deegan. “This is a pipe I can easily turn off. Not like when you build a housing development and then you’re stuck with all those houses and their impacts forever.”

Nitrogen additions were made by dissolving fertilizer in water, stored in large tanks like these.

photo courtesy of the TIDE Project

Climate change is perhaps the most all-encompassing of these involuntary experiments. As ArcticGRO’s and TIDEs results indicate, ecosystem responses to human disturbance, whether it is climate warming or nutrient over enrichment, are complex. Understanding and adapting to these responses will depend on continued monitoring, observation and experimentation.

A testament to the people

In the world of research, rife with limited grants and time-bound fellowships, ArcticGRO and TIDE have been uniquely successful. Research Associate, Hillary Sullivan, who has been part of the TIDE project since 2012, attributes this to the dedication of the researchers, who showed up year after year to get the research done even when funding wasn’t certain or while enduring a global pandemic.

“These large scale projects are a testament to the people that are involved in the effort, and the work that goes in behind the scenes to keep it running,” says Sullivan.

Suslova and Max Holmes on an Arctic river research trip.

photo by John LeCoq

Both ArcticGRO and TIDE plan to continue. ArcticGRO is seeking additional funding to analyze new chemical constituents and continue providing invaluable data for scientists and educators to understand how rivers are responding to a warming climate. “ArcticGRO has improved our understanding of the Arctic, and our work is just getting started,” says Zolkos. “Continuing will be essential for generating new insights on climate change, northern ecosystems, and societal implications.”

TIDE has now shifted to a new phase of study—observing the legacy of the added nitrogen on marsh recovery in the face of climate change induced sea level rise. Nitrogen additions were halted six years ago and researchers hope to gain insights into marsh restoration and ways to improve their resilience to sea level rise.

Thinking in the long-term is not something humans have historically excelled at, Deegan admits. But the more we try to expand our curiosity past immediate cause and effect, the better we get at understanding nature. If you want to understand an ecosystem, you have to think like an ecosystem—which means longer time scales and larger areas that encompass every aspect of the system.

“Nature tends to take the long view and people tend to take the short,” says Deegan. “So if you can stick with it for the long view, I think you see things in a very different way.”

Latest in Water

- In The News

Notes from an ecologist: Factoring in rivers and streams when studying bay health

- In The News