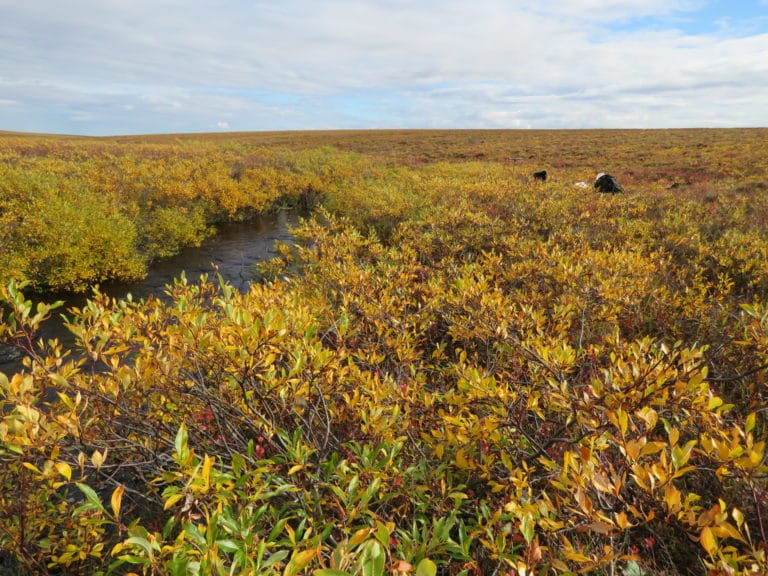

Expansion of tall shrubs points to larger Arctic change story

Tall shrubs have been expanding their coverage in the warming Arctic tundra region for decades. Now, a study led by Woodwell Climate Research Center scientist Dr. Anna Liljedahl shows that tall shrub expansion along riparian corridors is an indicator of major changes to permafrost, soil microbes, and river flows.

Researchers found streamside shrubs over five feet high are indicators of what are known as taliks—patches of unfrozen soil within permafrost that allow stream water to seep into the ground, potentially changing water systems for hundreds of miles downstream. The taliks fill with water in the summer when stream levels are high, then release their water in winter when precipitation is scarce and stream levels drop. This keeps flow downstream of the talik steadier year-round, while increasing the risk for streambeds to go dry above the talik in summer.

Above: photo courtesy of Anna Liljedahl

According to the study, the trend of increasing streamside tall shrubs point to widespread permafrost thaw reaching tens of meters beneath the stream that shifts tall shrub covered stream reaches towards losing water volume in summer. Conversely, a lack of tall shrubs points to what may be considered a more normal (gaining) stream reach, where the stream discharge increases downstream.

“Our team examined small streams north of Toolik, Alaska, and found the tall shrub cover along the streams coincides with taliks and losing streamflow conditions,” said Dr. Liljedahl. “They’re clear indicators of areas where stream water is seeping into these taliks—the higher the loss into the ground, the lower the streamflow downstream, and the more extensive shrub canopy (higher the leaf area index) along the streambank.” Dr Liljedahl thinks that it is possible that thriving tall shrubs require winter access to water (which the talik provides), something that was proposed by research study in Greenland and Scandinavia nearly 85 years ago and forgotten.

Based on the ample evidence of shrub expansion across the Arctic tundra in the literature, the researchers believe this trend has been occurring for decades in northern Alaska and elsewhere in the circumpolar Low Arctic. These new data may help researchers understand observed changes in Arctic river flows.

“These streams, which you can easily walk across, are the capillary of the Arctic hydrological system. They are small but many. If you add them up it is possible that they may be driving the changes documented in the large Arctic rivers,” said Dr. Liljedahl. “Larger rivers are seeing an increase in winter flow – is this phenomenon along small streams adding to that? What are the implications for water chemistry and temperature?”

There could be some benefits to the tall shrub expansion. More regular water flow could be good for fish, and the addition of cold water from the taliks could help counter rising stream water temperatures, while the tall shrub also shading the stream and keeping the temperatures cooler. Also, added vegetation provides a welcome food source for moose, beavers, and hare in the otherwise treeless tundra.

However, there are worrisome implications to these findings, which challenge a leading theory about permafrost thaw. Current theory holds that shrubs initiate talik development due to the accumulation of snow around tall shrubs that keeps the ground below warm in winter, promoting permafrost thaw. But the study by Dr. Liljedahl’s team suggests it’s the permafrost thaw and taliks that come first and that the winter access of talik-water that allows tall shrubs to thrive and grow into tree-size on the tundra landscape. If that is the case, it suggests permafrost thaw in the cold continuous permafrost region began earlier and has been more widespread than previously thought.

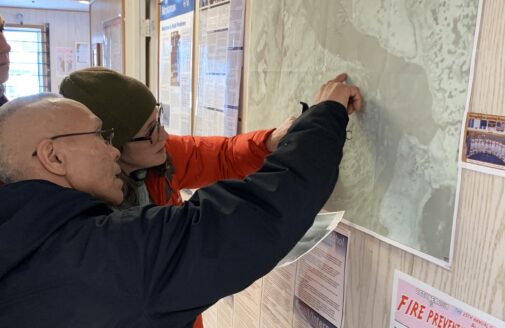

Above: photo courtesy of Anna Liljedahl

This study was made possible with support from the National Science Foundation’s Arctic System Science Program EArly-concept Grants for Exploratory Research (EAGER).