Enduring scientific partnership examines Congo River

[Updated July 7, 2020]

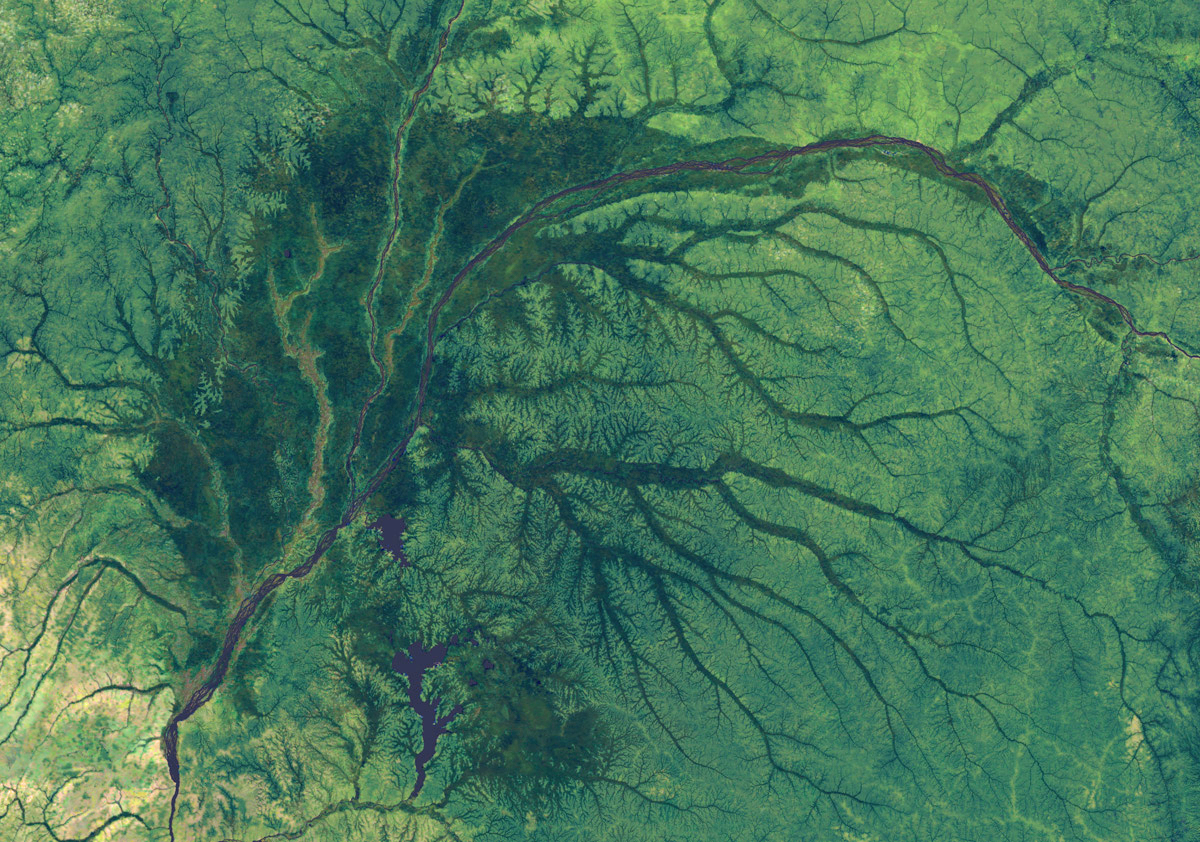

The Congo River represents the world’s second largest watershed, and it is one that has seen dramatic changes in recent years. As a founding member of the Global Rivers Observatory, Woodwell Climate Research Center, has been working with researchers in the Republic of Congo to track those changes, collecting water samples and analyzing the chemical composition for over a decade.

The Congo River divides the Republic of Congo on its east bank from the Democratic Republic of Congo on its west bank. In recent years, there’s been renewed talk of diverting water from the Ubangi River, a key Congo River tributary, hundreds of miles to Lake Chad, which has been dropping due to unsustainable human withdrawals. Bienvenue Dinga, a hydrologist and Woodwell Climate’s research partner in the Republic of Congo, is fighting that effort to protect the communities that depend on the Congo River Basin’s waters for food and transportation.

Above: Bienvenue Dinga working with Postdoctoral Researcher Scott Zolkos

Dinga visited Falmouth in February, bringing Congo River water samples to Woodwell Climate Research Center’s environmental chemistry laboratory and meeting with staff to discuss progress. He is head of the National Hydrological Service of Congo, as well as a lecturer and researcher at Marien Ngouabi University. He has partnered with Woodwell Climate and the Global Rivers Observatory since 2010, collecting monthly samples from the main stem of the Congo River. Dinga manages a staff of 18, with Woodwell Climate funds supplying equipment and enabling training of new researchers. He’s published papers with Woodwell Climate Deputy Director Dr. Max Holmes and other scientists in the Woods Hole community.

Holmes first met Dinga a decade ago, when he applied for a research permit to sample rivers in the Republic of Congo. The government assigned Dinga as Woodwell’s local scientist and guide, a move that immediately paid dividends when the team’s plane was disabled. Dinga arranged for a truck to make the trip and negotiated accommodations (he speaks six languages), allowing the team to take samples along the entire route and get a once-in-a-lifetime experience of life inside the Republic of Congo.

Though the Congo River Basin is second only to the Amazon in terms of discharge, it has historically been studied much less than the Amazon. During a decade working with Woodwell Climate, Dinga says he’s seen evidence of a changing climate manifest in river discharge and chemistry.

“In addition to providing equipment and access to the best analysis, [Woodwell Climate]’s consistent support has enabled us to build historical data, which we didn’t have before. Studying a river requires a large, years-long data set and we’re just now getting to the point where we can see trends,” said Dinga. “When I return home with this data, our government ministry is very happy.”

“Studying a river requires a large, years-long data set and we’re just now getting to the point where we can see trends.”

Bienvenue Dinga

In addition to supporting local decision-making, this long-running dataset enables Woodwell Climate Research Center and partners to bring new insights to global phenomena, such as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Sargassum is a brown algae found in the tropical ocean—that washes up on coastlines in large waves that can limit fishers access to water and fatally prevent marine mammals from surfacing for air. Nutrient inputs from the Congo and Amazon Rivers may play a role in causing the sargassum bloom in the Caribbean.

“Because we have 10 years of data on both of these rivers, we’re in a much better position to determine whether they play a role. In a sense, this shows the value of long term data sets like this,” said Holmes.

To learn more about the Global Rivers Observatory’s ongoing work studying the Congo River, visit GlobalRivers.org/Congo.

Latest in Tropics

- In The News

To meet pledges to save forests spending must triple, U.N. report says

- In The News