Deciphering patterns in the dirt

Growing up on a dairy farm, observing a potential climate solution within America’s rangelands

Dr. Jennifer Watts records carbon flux measurements to help refine a model of rangeland soil carbon.

photo by Sarah Ruiz

At age 12, Woodwell Assistant Scientist, Dr. Jennifer Watts was accustomed to black dirt—the rich, wet, crumbling, fertile stuff she dug through on her family’s hobby farm in Oregon. But after moving with her parents and siblings to a roughly 224-acre dairy farm in Minnesota, all she saw around her was light brown, dry earth.

“A lot of the farms around us were a mix of dairy farms and really intense cropping rotations of corn and soybean,” Dr. Watts says. “And I started to notice, where there was tillage, how depleted the soil looked.”

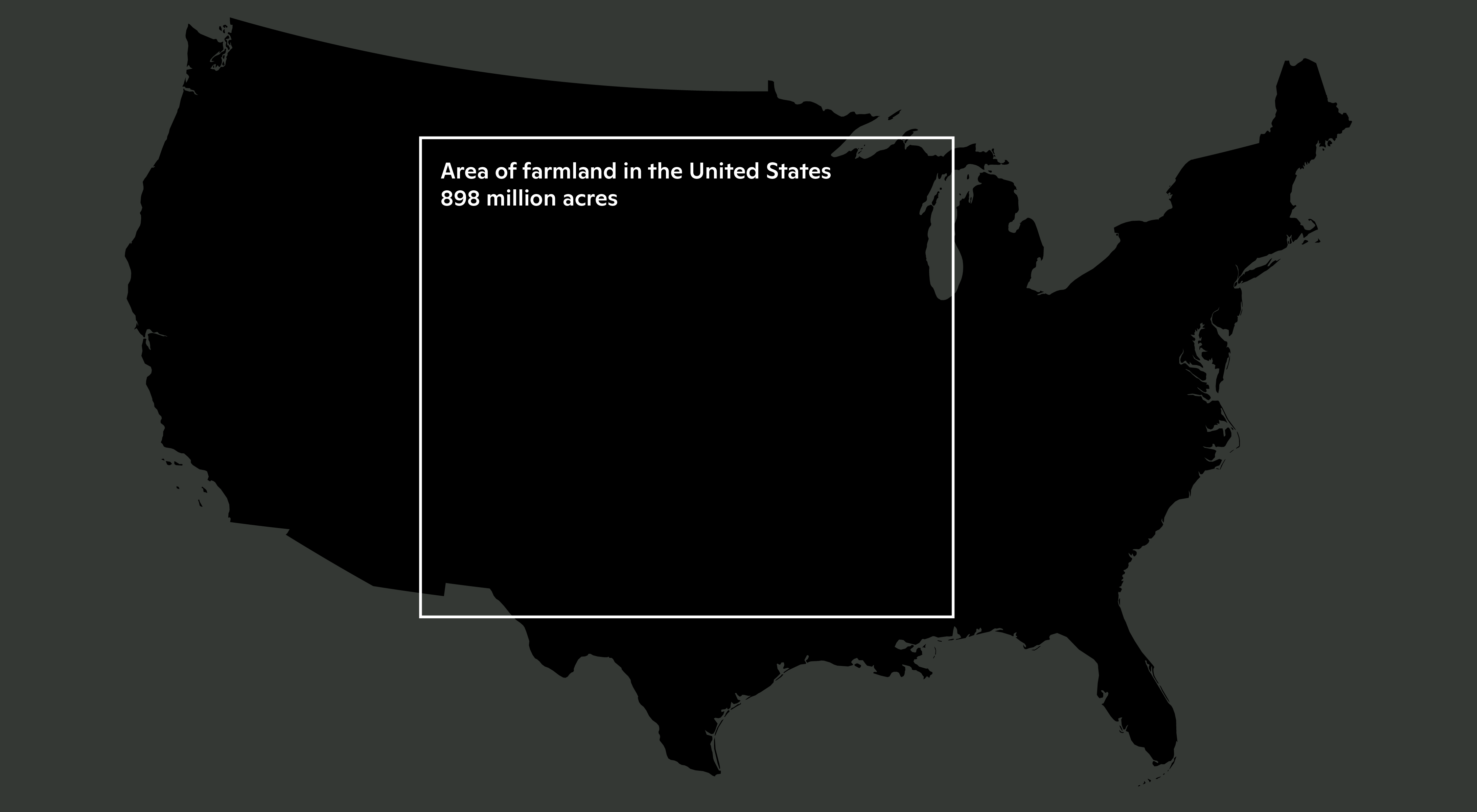

In the United States, farmland covers more than 895 million acres (an area larger than the size of India), and it has a proportionately massive footprint on the environment. Intensive agriculture pulls nutrients out of the soil and doesn’t always return them, converting natural grasslands into monocultures and releasing large amounts of stored carbon in the process.

map by Greg Fiske and Christina Shintani

But what Dr. Watts saw throughout a childhood spent tending to her family’s farm, was that changing the way agricultural land is managed can sometimes reverse those impacts. In converting their cropland to pasture, to support an organic, grass-based dairy farm, Dr. Watts and her family stumbled upon the principles of regenerative agriculture. A practice that can produce food in a way that works with the ecosystem, rather than against it, and has implications for climate mitigation as well.

“It became, for me, an unintentional transformative experiment that my family conducted on our farm,” Dr. Watts says. “By the time I graduated high school, our lands were so lush and green. It was a healthy, productive, diverse ecosystem again.”

Dr. Watts’ family farm.

photo courtesy of Jennifer Watts

Going rogue on the range

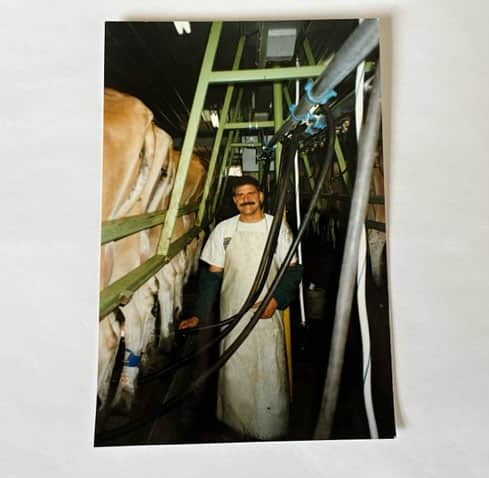

When Dr. Watts talks about her father’s idea to move to central Minnesota and start a dairy farm, she calls him a “rogue.” Originally from Alaska, he intended to work in fisheries, but had to change course after a cannery accident. Searching for something that would allow him to still spend his days outside, he settled on farming.

Dr. Watt’s father, John Watts, milking cows.

photo courtesy of Jennifer Watts

From the beginning, the Watts’ farming practices were considered unconventional in their rural Minnesota community. Firstly, they planted wild grasses and legumes like clover and alfalfa. Then, they left it alone. No tilling in the springtime alongside their neighbors; they simply let the plants establish themselves and moved the cattle frequently (with the help of a cow dog named Annie) to avoid overgrazing.

“After the first couple of years, I started noticing we had a lot more biological diversity in our fields, relative to our neighbors. We had a lot more bees buzzing, and butterflies, and we were popular with the deer and ducks,” Dr. Watts says. A few more years, and the soil started becoming dark and earthy-smelling again, like the soil she remembered from Oregon.

Degraded soils (left) and more productive soils (right) often differ in coloration, moisture and texture.

photos by Sarah Ruiz

What was happening on their “rogue” dairy farm, was a gradual, partial reclamation of a lost grassland ecosystem—one that used to stretch across the midwest United States and was tended by native grazing species like bison or elk. Grazing plays a major role in cycling nutrients back into the soil, building up important elements like carbon and nitrogen. The near extinction of bison and the proliferation of monoculture cropping have broken this cycle—but cows have the potential to fill the gap left by ancient grazers, re-starting that process. Simple adjustments to management techniques, like lengthening time between grazing a pasture, can give the land time to recover.

Storing carbon in the soil

This also has implications for how we combat climate change—a term Dr. Watts wasn’t familiar with until later in high school, when family trips back to Alaska revealed the glaciers she loved to visit were shrinking.

“Seeing the glaciers was our favorite thing to do with my grandma, but they were beginning to disappear. And one year, suddenly, I noticed these informational panels along the walk exiting the National Park talking about this thing called climate change,” says Dr. Watts.

Dr. Watts was also seeing another pattern emerge on the farms in her midwest community. Water was becoming a little scarcer. Many of the farms around her family’s had begun investing in irrigation—something that was previously unnecessary, and remained so for the Watts’ farm. Their rich, black soil held onto the water for longer.

A ranch hand on Valdez Ranch in Colorado lays out PVC tubes to irrigate a pasture.

photo by Sarah Ruiz

As she grew up and (with the help of a pre-Google web search over dial-up internet) charted a course for her career as an ecologist, Dr. Watts began to study the science underlying these patterns she was noticing, and connected them to climate change.

Growing plants draw carbon from the atmosphere. When plants die and decay, some of that carbon is released to the air to be drawn back down again by a new season of growth, while some is stored away as organic matter in the soil. Over centuries, this process forms a stable sink of carbon on the land. Regenerative grazing—the way the Watts family did it—stimulates more plant growth to keep this cycle turning, while overgrazing or removing grazers entirely can halt the process, allowing for erosion, less healthy root systems, and the degradation of the carbon sink. In the U.S., rangelands have historically contributed more to the depletion of soil carbon, but Dr. Watts’ research with Woodwell has demonstrated that, with proper management, rangelands and other agricultural lands have the potential to contribute positively to the climate equation again.

Seeing patterns from a new perspective

For the past two summers, Dr. Watts, alongside the Woodwell Rangelands team and collaborators, has driven across the western U.S. to collect biomass and soil samples and measure carbon flux from working ranches and federal grazing leases in Montana, Colorado, and Utah.

These measurements will help calibrate a new satellite remote sensing-informed model that can track how much carbon is being stored on grazing lands. The model will be hosted on the Rangeland Carbon Management Tool(RCMT) platform—a new web application she and researchers at both Woodwell and Colorado State University are developing to give land managers access to carbon and other ecosystem data for their lands.

The idea is that, with a tool like this in hand, ranchers can account for carbon dioxide flowing into and out of the rangeland ecosystem, and track how this changes over time in response to land management adjustments. It will also show changes in correlating ecosystem metrics like plant diversity and productivity, as well as soil moisture—two things that are crucial to maintaining a healthy and economically viable range. With this information, Dr. Watts and colleagues hope to encourage a regional shift in ranch management strategies that protect and rebuild stores of soil carbon, while providing ranchers with essential co-benefits.

Dr. Watts has been working with Jim Howell, owner of sustainable land management company Grasslands LLC, to connect with individual ranchers and discuss how a tool like this could help their operations. Though ranchers can be a tradition-bound group, Dr. Watts says seeing data that confirms their anecdotal experiences of hotter winters, drier summers, longer droughts, and other climate-related changes has opened them up to making changes.

“There are so many times when we just see the ‘aha moment’ in the manager or the land owner’s face, because they’re suddenly able to see these patterns from a very different perspective,” says Dr. Watts. “Most people, we have strong memories, we know that something’s different, but to be able to show that through data and not only memories—it’s so powerful.”

(below left) Dr. Watts with a calf and (right) her father on their farm.

photos courtesy of Jennifer Watts

(bottom) Dr. Watts on Valdez Ranch, Colorado.

photo by Sarah Ruiz

Building climate solutions on the ground

In addition to ecosystem co-benefits, storing carbon on rangelands could have direct economic benefits for ranchers as well. The RCMT will provide baseline data that could be used to verify credits within a voluntary soil carbon market. Rangelands historically haven’t been included in carbon markets because of gaps in monitoring data that the RCMT will help fill. The data could also be useful for local or state governments setting up payments for ecosystem services schemes in their region that would provide money directly to ranchers in exchange for storing carbon on their lands.

Of course, cattle aren’t without their complications, and ranching practices are just one element of a global meat and dairy industry that contributes to 15 percent of global emissions. But Dr. Watts’ roots as a dairy farmer make her enthusiastic about the possibilities this solution holds to both mitigate emissions and keep an important American livelihood resilient as climate conditions change.

“It’s just one aspect in this really complicated global system,” says Dr. Watts. “But if we manage our ecosystems better, building more intact environments where we can, this can sequester more carbon while restoring ecosystem health and productivity. It’s not the solution, but it is a solution that can benefit our planet while supporting rural communities.”

Rangeland Carbon Management Tool research is funded in part by Conscience Bay Research, in partnership with Western States Ranches.