New legislation proposed in the U.S. Senate would for the first time consider the importance of monitoring permafrost thaw as part of a broader effort to improve U.S. weather forecasting and modeling, and support cutting-edge tools and resources to better track this serious environmental hazard in the North.

Read more on Permafrost Pathways.

Thawing Alaskan permafrost is unleashing more mercury, confirming scientists’ worst fears

“It has that sense of a bomb that’s going to go off.”

Alaska’s permafrost is melting and revealing high levels of mercury that could threaten Alaska Native peoples.

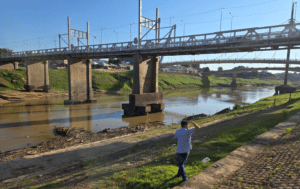

That’s according to a new study released earlier this month by the University of Southern California, analyzing sediment from melted permafrost along Alaska’s Yukon River.

Researchers already knew that the Arctic permafrost was releasing some mercury, but scientists weren’t sure how much. The new study — published in the journal Environmental Research Letters — found the situation isn’t good: As the river runs west, melted permafrost is depositing a lot of mercury into the riverbank, confirming some of scientists’ worst estimates and underscoring the potential threat to the environment and Indigenous peoples.

Fire is a necessary element in northern forests, but with climate change, these fires are shifting to a far less natural regime— one that threatens the ecosystem instead of nurturing it.

Boreal tree species, like black spruce, have co-evolved over millennia with a steady regime of low-frequency, high-intensity fires, usually ignited by lightning strikes. These fires promote turnover in vegetation and foster new growth. On average, every 100 to 150 years, an intense “stand-replacing” fire might completely raze a patch of forest, opening a space for young seedlings to take root.

But rapid warming in northern latitudes has intensified this cycle, sparking large fires on the landscape more frequently, jeopardizing regeneration, and releasing massive amounts of carbon that will feed additional warming. Here’s how climate change is impacting boreal fires.

Climate Impacts on Boreal Fire

In order for a fire to start, you need three things— favorable climatic conditions, a fuel source, and an ignition source. These elements, referred to as the triangle of fire, are all being exacerbated as boreal forests warm, resulting in a fire regime with much larger and more frequent fires than the forests evolved with.

Climate conditions

Forest fires only ignite in the right conditions, when high temperatures combine with dryness in the summer months. As northern latitudes warm at a rate three to four times faster than the rest of the globe, fire seasons in the boreal have lengthened, and the number of fire-risk days have increased.

In some areas of high-latitude forest, climate change has changed the dynamics of snowfall and snow cover disappearance. The rate of spring snowmelt is often an important factor in water availability on a landscape throughout the summer. A recent paper, led by Dr. Thomas Hessilt of Vrije University in collaboration with Woodwell Associate Scientist, Dr. Brendan Rogers, found that earlier snow cover disappearance resulted in increased fire ignitions. Early snow disappearance was also associated with earlier-season fires, which were more likely to grow larger— on average 77% larger than historical fires.

Fuel

The second requirement for fires to start is available “fuel”. In a forest, that’s vegetation (both living and dead) as well as carbon-rich soils that have built up over centuries. Here, the warming climate plays a role in priming vegetation to burn. A paper co-authored by Rogers has demonstrated temperatures above approximately 71 F in the forest canopy can be a useful indicator for the ignition and spread of “mega-fires,” which spread massive distances through the upper branches of trees. The findings suggest that heat-stressed vegetation plays a big role in triggering these large fires.

Warming has also triggered a feedback loop around fuel in boreal systems. In North America, the historically dominant black spruce is struggling to regenerate between frequent, intense fires. In some places, it is being replaced by competitor species like white spruce or aspen, which don’t support the same shaded, mossy environment that insulates frozen, carbon-rich soils called permafrost, making the ground more vulnerable to deep-burning fires. When permafrost soils thaw and burn, they release carbon that has been stored—sometimes for thousands of years—contributing to the acceleration of warming.

Ignition

Finally, fires need an ignition source. In the boreal, natural ignitions from lightning are the most frequent culprit, although human-caused ignitions have become more common as development expands into northern forests.

Because of lightning’s ephemeral nature, it has been difficult to quantify the impacts of climate change on lightning strikes, but recent research has shown lightning ignitions have been increasing since 1975, and that record numbers of lightning ignitions correlated with years of record large fires. Some models indicate summer lightning rates will continue to increase as global temperatures rise.

There is also evidence showing that a certain type of lightning— one more likely to result in ignition— has been increasing. This “hot lightning” is a type of lightning strike that channels an electrical charge for an extended period of time and tends to correlate more frequently with ignitions. Analysis of satellite data suggests that with every one degree celsius of the Earth’s warming, there might be a 10% increase in the frequency of these hot lightning strikes. That, coupled with increasingly dry conditions, sets the stage for more frequent fire ignitions.

Fire Management as a Climate Solution

So climate change is intensifying every side of the triangle of fire, and the combined effects are resulting in more frequent, larger, more intense blazes that contribute more carbon to the atmosphere. While the permanent solution to bring fires back to their natural regimes lies in curbing global emissions, research from Woodwell Climate suggests that firefighting in boreal forests can be a successful emissions mitigation strategy. And a cost effective one too— perhaps as little as $13 per metric ton of carbon dioxide avoided, which puts it on par with other carbon mitigation solutions like onshore wind or utility-scale solar. It also has the added benefit of protecting communities from the health risk of wildfire smoke.

Rogers, along with Senior Science Policy Advisor, Dr. Peter Frumhoff, and Postdoctoral researcher Dr. Kayla Mathes have begun work in collaboration with the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska to pilot this solution as part of the Permafrost Pathways project. Yukon Flats is underlain by large tracts of particularly carbon-rich permafrost soils, making it a good candidate for fire suppression tactics to protect stored carbon.

The project will be the first of its kind— working with communities in and around the Refuge as well as US agencies to develop and test best practices around fighting boreal fires specifically to protect carbon. Broadening deployment of fire management could be one strategy to mitigate the worst effects of intensifying boreal fires, buying time we need to get global emissions in check.

Acre’s communities face drinking water shortage amid Amazon drought

Rosineide de Lima, a resident of the Panorama community in Rio Branco, in the state of Acre, faces a daily struggle for survival amid the severe drought that has hit Acre’s capital and surrounding region. In her house, where seven people live, water is rationed daily. “My well will run dry in August,” she told Mongabay, worried about the health of her five children. “For now, I’m still managing to get some water from it to wash clothes once a week and do household chores, but for drinking I’ve started buying mineral water since my children started having health problems, such as dehydration.”

After experiencing an extreme drought in 2023, the Amazon is already feeling signs of a new drought this year. According to experts, the 2024 drought could be even worse. It has already affected 69% of the Amazon’s municipalities, an increase of 56% compared with the same period in 2023.

N.W.T.’s Scotty Creek Research Station rebuilt, now with its own fire-protection system

Peter Cazon of Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation says he’s ready to start up sprinklers at ‘drop of a dime’

Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation is preparing for the grand reopening of the Scotty Creek Research Station in the N.W.T. later this month. The site was almost entirely gutted by wildfire two years ago, and now the First Nation has taken steps to keep that from happening again.

Peter Cazon, a land guardian for the Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation (LKFN), has applied his more than two decades of experience in fighting forest fires to the task. He said he’s built a 75-metre-wide firebreak around the camp, and has helped set up a sprinkler system.

If pilots flying in the area notice fire, Cazon said they’ll call into the community’s airport and soon after he’ll be notified of the threat.