As climate threats escalate, Rep. Leger Fernández leads charge to weather-proof America’s energy grid

Bill would create a first-of-its-kind federal weather data platform to help utilities prevent blackouts and protect families from extreme climate events.

As wildfires rage, floods surge, and power grids strain under record-breaking heat, U.S. Representatives Leger Fernández (NM-03), Casten (IL-06), Castor (FL-11), and Ross (NC-02) introduced the Weather-Safe Energy Act of 2025. This landmark bill will equip utilities with the cutting-edge weather data, modeling, and support they need to withstand the growing threat of extreme weather. The bill addresses a critical need at a time when the nation’s energy infrastructure faces unprecedented threats from increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather events, including hurricanes, wildfires, flooding, and droughts. Utilities and grid operators currently lack the sophisticated weather data and modeling tools necessary to prepare for these cascading risks.

Read more on Rep. Leger Fernández’s website.

Despite a warming climate, disruptive winter cold spells still invade the U.S., and a new study helps explain why. Researchers found that two specific patterns in the stratospheric polar vortex, a swirling mass of cold air high above the Arctic, can steer extreme cold to varying regions of the country. One pattern drives Arctic air into the northwestern U.S., and the other into central and eastern areas. Since 2015, the Northwest has experienced more of these cold spells owing to a shift in stratospheric behavior tied to a warming climate – more proof that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.

As winters in the United States continue to warm on average, extreme cold snaps still manage to grip large swaths of the country with surprising ferocity. A new study offers a powerful clue: the answer may lie more than 10 miles above our heads, in the shifting patterns of the stratosphere.

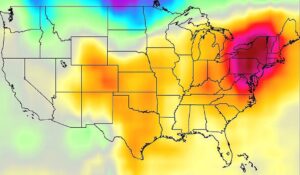

The research reveals how two specific patterns in the stratospheric polar vortex—a high-altitude pool of frigid air over the Arctic encircled by a band of strong west winds—can contribute to bone-chilling weather events across regions of North America. The patterns are described as “stretched” because the vortex is elongated relative to its typical, more circular shape. One such pattern reinforces intense cold in the northwestern US, while the other variation takes aim at central and eastern states. Both patterns are associated with changes in how atmospheric waves, in both the stratosphere and lower atmosphere, can alter the jet stream and allow Arctic air to penetrate far southward.

“Understanding the stratosphere’s fingerprints on changing weather patterns–particularly the counterintuitive connections between a warming globe and extreme cold weather events–could improve long-range forecasting, allowing cities, power grids, and agriculture to better prepare for winter extremes,” said Dr. Jennifer Francis.

Life-threatening heat domes confounding forecasters

Record-breaking temperatures seared the eastern US last month, leading to power emergencies across the region. The cause: an enormous ridge of high pressure that settled on the region, known as a heat dome.

This phenomenon has also already struck Europe and China this summer, leading to the temporary closure of the Eiffel Tower and worries about wilting rice crops, respectively. But while heat domes are easy to identify once they strike, they remain difficult to forecast — a problematic prospect in a warming world.

When I started at Woodwell Climate, I had very little personal or professional experience with boreal wildfire. I was a forest ecologist drawn to this space by the urgency of the climate crisis and the understanding that northern ecosystems are some of the most threatened and critical to protect from a global perspective. More severe and frequent wildfires from extreme warming are burning deeper into the soil, releasing ancient carbon and accelerating permafrost thaw. Still largely unaccounted for in global climate models, these carbon emissions from wildfire and wildfire-induced permafrost thaw could eat up as much as 10% of the remaining global carbon budget. More boreal wildfire means greater impacts of climate change, which means more boreal wildfire. But when I joined the boreal fire management team at Woodwell, the global picture was the extent of my perspective.

This past June, under a haze of wildfire smoke with visible fires burning across the landscape, Woodwell Climate’s fire management team made our way back to Fort Yukon, Alaska. Situated in Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge at the confluence of the Yukon and Porcupine Rivers, this region is home to Gwich’in Athabascan people who have been living and stewarding fire on these lands for millennia. Our time there was brief, but it was enough to leave us humbled by the reality that the heart of the wildfire story—both the impacts and the solutions—lie in communities like Fort Yukon.

We listened to community members and elders tell stories about fire, water, plants, and animals, all of which centered around observations of profound change over the past generation. As we shared fire history maps at the Gwichyaa Zhee Giwch’in tribal government office, we were gently reminded that their knowledge of changing wildfire patterns long preceded scientists like us bringing western data to their village. We learned that fire’s impact on critical ecosystems also affects culture, economic stability, subsistence, and traditional ways of life. Increasing smoke exposure threatens the health of community members, particularly elders, and makes the subsistence lifestyle harder and more dangerous. A spin on the phrase “wildland urban interface,” Woodwell’s Senior Arctic Lead Edward Alexander coined the phrase “wildland cultural interface,” which brilliantly captures the reality that these fire-prone landscapes, culture, and community are intertwined in tangible and emotional ways for the Gwich’in people.

“There’s too much fire now” was a common phrase we heard from people in Fort Yukon. Jimmy Fox, the former Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge (YFNWR) manager had been hearing this from community members for a long time, along with deep concerns about the loss of “yedoma” permafrost, a type of vulnerable permafrost with high ice and carbon content widespread throughout the Yukon Flats. With the idea originating from a sharing circle with Gwich’in Council International, in 2023 Jimmy enacted a pilot project to enhance the fire suppression policy of 1.6 million acres of yedoma land on the Yukon Flats to explicitly protect carbon and climate, the first of its kind in fire management policy. He was motivated by both the massive amount of carbon at risk of being emitted by wildfire and the increasing threats to this “wildland cultural interface” for communities on the Yukon Flats.

Ever since I met Jimmy, I have been impressed by his determination to use his agency to enact powerful climate solutions. Jimmy was also inspired by a presentation from my postdoctoral predecessor, Dr. Carly Phillips, who spoke to the fire management community about her research showing that fire suppression could be a cost-efficient way to keep these massive, ancient stores of carbon in the ground. Our current research is now focused on expanding this analysis to explicitly quantify the carbon that would be saved by targeted, early-action fire suppression strategies on yedoma permafrost landscapes. This pilot project continues to show the fire management community that boreal fire suppression, if done with intention and proper input from local communities, can be a climate solution that meets the urgency of this moment.

“Suppression” can be a contentious word in fire management spaces. Over-suppression has led to fuel build up and increased flammability in the lower 48. But these northern boreal forests in Alaska and Canada are different. These forests do not have the same history of over-suppression, and current research suggests that the impacts of climate change are the overwhelming driver of increased fire frequency and severity. That said, fire is still a natural and important process for boreal forests. The goal with using fire suppression as a climate solution is never to eliminate fire from the landscape, but rather bring fires back to historical or pre-climate change levels. And perhaps most importantly, suppression is only one piece of the solution. The ultimate vision is for a diverse set of fire management strategies, with a particular focus on the revitalization of Indigenous fire stewardship and cultural burning, to cultivate a healthier relationship between fire and the landscape.

The boreal wildfire problem is dire from the global to local level. But as I have participated in socializing this work to scientists, managers, and community leaders over the past year, from Fort Yukon, Alaska to Capitol Hill, I see growing enthusiasm for solutions that is not as widely publicized as the crisis itself. I see a vision of Woodwell Climate contributing to a transformation in boreal fire management that has already begun in Indigenous communities, one that integrates Indigenous knowledge and community-centered values with rigorous science, and ends with real reductions in global carbon emissions. Let’s begin.

NASA Earth Science Division provides key data

In May, the US Administration proposed budget cuts to NASA, including a more than 50% decrease in funding for the agency’s Earth Science Division (ESD) (1), the mission of which is to gather knowledge about Earth through space-based observation and other tools (2). The budget cuts proposed for ESD would cancel crucial satellites that observe Earth and its atmosphere, gut US science and engineering expertise, and potentially lead to the closure of NASA research centers. As former members of the recently dissolved (3) NASA Earth Science Advisory Committee, and all-volunteer, independent body chartered to advise ESD (4), we warn that these actions would come at a profound cost to US society and scientific leadership.

The science behind Texas’ catastrophic floods

At least 95 people died in the flash floods. The disaster has the fingerprints of climate change all over it.

Last month in Dakar, Senegal, Woodwell Climate Associate Scientist Glenn Bush and Forests & Climate Change Coordinator Joseph Zambo facilitated a high-level workshop with the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Director of Climate Change, Aimé Mbuyi, lead scientist on the country’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) reporting process, Prof. Onesphore Mutshaili, and project consultant Melaine Kermarc. The goal of the workshop was to begin generating a clear set of priorities for the next 5 years for stepping up the ambition of the country’s NDCs, and to discuss strategies for monitoring and reporting on emissions.

Under the Paris Agreement, each country is required to submit to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change a detailed description of their emissions reduction commitments and then regular reports on progress. Currently, DRC has pledged to reduce emissions by 21% by 2030, focusing on reform in their energy, agriculture, forestry, and other land use sectors. While NDCs are intended to represent a country’s highest possible ambition, DRC is looking to step up further. Officials are at work developing a plan to reach net-zero emissions, which would place the country among the leaders of climate policy in Africa.

In order to do this, DRC needs a reliable framework for measuring and monitoring emissions, so that progress can be accurately reported on. At the workshop, Bush, Mbuyi, Zambo, Kermarc and Mutshaili discussed ways to strengthen the NDC reporting process. Among the top needs identified was stronger institutional scientific capacity, increased coordination and data sharing, and more funding and awareness of the process at local and provincial levels.

“High quality data is essential to building a high integrity NDC,” says Bush. “Improving the scope and quality of data available to monitor carbon will not only help the country meet the highest tier of reporting standards, but also access performance-based payment mechanisms to help finance the transition to a low emissions economy.”

Through their conversations about challenges and opportunities, the group identified three areas for intervention that will help the country navigate towards a stronger emissions reduction plan. These recommendations were outlined in a report on the workshop proceedings.

- Improved governance and policy management: Establishing a National Climate Change Council to better integrate climate policy into national development plans.

- Science-backed carbon accounting and budgeting: Developing credible data standards for measuring emissions and ecosystem services to support transparent and effective reporting on climate performance.

- Cross-sectoral integration: Promoting emissions reductions across all sectors through collaborative partnerships, particularly in the field of climate-smart agriculture and carbon payment mechanisms.

Mr Aimé Mbuyi, Head of the Climate Change Division (CCD) at the DRC’s Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development, declared that “these recommendations reflect an important set of practical steps to move from aspiration to operational reality in order to increase the financing and impact to conserve our forests and stimulate sustainable development in the DRC”.

Woodwell Climate Research Center has been a long time partner of the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development. The Center is assisting the ministry in laying the technical foundations to support the NDC improvement process and helping build in-country scientific capacity to make a net-zero emissions plan a reality. This and other partnerships will be essential in transitioning the DRC to a low-carbon economy.

“We appreciated the long-standing trust that has developed over years of formal and informal collaboration on climate policy,” said Mbuyi. “The scientific partnership with Woodwell is invaluable to us at CCD, providing actionable information that has proven essential to advancing the climate mitigation and adaptation agenda.”