For 1st time, fires are biggest threat to forests’ climate-fighting superpower

Forests play a major role pulling planet-warming carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. As the world heats up, some forests are becoming emitters in their own right.

In 2023 and 2024 the world’s forests absorbed only a quarter of the carbon dioxide they did in the beginning of the 21st century, according to data from the World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Watch.

Those back-to-back years of record-breaking wildfires hampered forests’ ability to tuck away billions of tons of carbon dioxide, curbing some of the global warming caused by emissions from burning fossil fuels.

Keep reading on The New York Times.

Woodwell Climate Conversations: Turning the Tide

Climate Progress, Peril, and the Path Ahead

Join Gina McCarthy and Max Holmes for a timely conversation on how bold, science-based action drove historic progress—and what’s at stake as that progress faces new political threats.

Notes from an ecologist: Factoring in rivers and streams when studying bay health

On the morning of July 7, more than a hundred volunteers from Buzzards Bay Coalition Baywatchers fanned out to the more than 30 small embayments that surround Buzzards Bay to collect the first round of this summer’s four sets of water quality samples.

By mid-afternoon we had large and small bottles from more than 200 different stations lined up on the tables at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, where the samples enter an assembly line of different laboratory analyses that include different forms of nitrogen and the concentration of chlorophyll—the main pigment in algae and an excellent metric of the amount of algae in the water.

Read more on The Falmouth Enterprise.

As climate threats escalate, Rep. Leger Fernández leads charge to weather-proof America’s energy grid

Bill would create a first-of-its-kind federal weather data platform to help utilities prevent blackouts and protect families from extreme climate events.

As wildfires rage, floods surge, and power grids strain under record-breaking heat, U.S. Representatives Leger Fernández (NM-03), Casten (IL-06), Castor (FL-11), and Ross (NC-02) introduced the Weather-Safe Energy Act of 2025. This landmark bill will equip utilities with the cutting-edge weather data, modeling, and support they need to withstand the growing threat of extreme weather. The bill addresses a critical need at a time when the nation’s energy infrastructure faces unprecedented threats from increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather events, including hurricanes, wildfires, flooding, and droughts. Utilities and grid operators currently lack the sophisticated weather data and modeling tools necessary to prepare for these cascading risks.

Read more on Rep. Leger Fernández’s website.

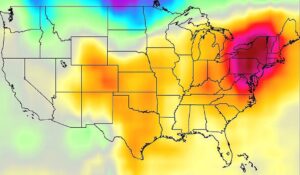

Life-threatening heat domes confounding forecasters

Record-breaking temperatures seared the eastern US last month, leading to power emergencies across the region. The cause: an enormous ridge of high pressure that settled on the region, known as a heat dome.

This phenomenon has also already struck Europe and China this summer, leading to the temporary closure of the Eiffel Tower and worries about wilting rice crops, respectively. But while heat domes are easy to identify once they strike, they remain difficult to forecast — a problematic prospect in a warming world.

NASA Earth Science Division provides key data

In May, the US Administration proposed budget cuts to NASA, including a more than 50% decrease in funding for the agency’s Earth Science Division (ESD) (1), the mission of which is to gather knowledge about Earth through space-based observation and other tools (2). The budget cuts proposed for ESD would cancel crucial satellites that observe Earth and its atmosphere, gut US science and engineering expertise, and potentially lead to the closure of NASA research centers. As former members of the recently dissolved (3) NASA Earth Science Advisory Committee, and all-volunteer, independent body chartered to advise ESD (4), we warn that these actions would come at a profound cost to US society and scientific leadership.

The science behind Texas’ catastrophic floods

At least 95 people died in the flash floods. The disaster has the fingerprints of climate change all over it.

Brazil wants to scale up regenerative tropical agriculture model (Portuguese)

Model developed by Brazilian entities was presented at a conference in Germany preceding COP30

Brazilian researchers presented this Saturday (21/6), in a parallel event to the Bonn Conference in Germany , a new sustainable model for the development of regenerative tropical agriculture. The initiative is led by the Dom Cabral Foundation, but brings together private companies and civil society entities as partners.

The business model designed to accelerate the transition from traditional systems to regenerative agriculture in the planet’s tropical belt includes pillars such as production diversification, soil health, use of biological inputs and a focus on the socioeconomic development of producers.