photo by Linda Deegan

- Zhongqi Chen Research Scientist

- Linda A. Deegan Senior Scientist

- Robert Vincent Assistant Director, Advisory Services for the MIT Sea Grant College Program, Marine Advisory Group

- Sara Beery Assistant Professor, MIT EECS

- Dale Oakley Assistant Director of Natural Resources, Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

- Wendi Buesseler President, Coonamessett River Trust

- Timm Haucke PhD student, MIT CSAIL

- Lydia Zuehsow MIT Lincoln Laboratory

- Austin Powell

- Kevin Bennett MIT Sea Grant

- Sydney Keane Natural Resources, Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

River herring population levels are at historic lows, threatening ecosystem health and biodiversity.

River herring, including Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and Blueback (Alosa aestivalis), are anadromous species, meaning they migrate between freshwater and marine ecosystems. They contribute significantly to nutrient cycling and serve as a crucial food source for various predators.

Over the centuries, river herring populations have dramatically declined due to habitat degradation, overfishing, and the construction of dams, which block their migratory routes and disrupt spawning.

Monitoring river herring populations is a key aspect of restoration efforts, as it provides the critical data needed to track population trends, inform management strategies, and guide an effective restoration program.

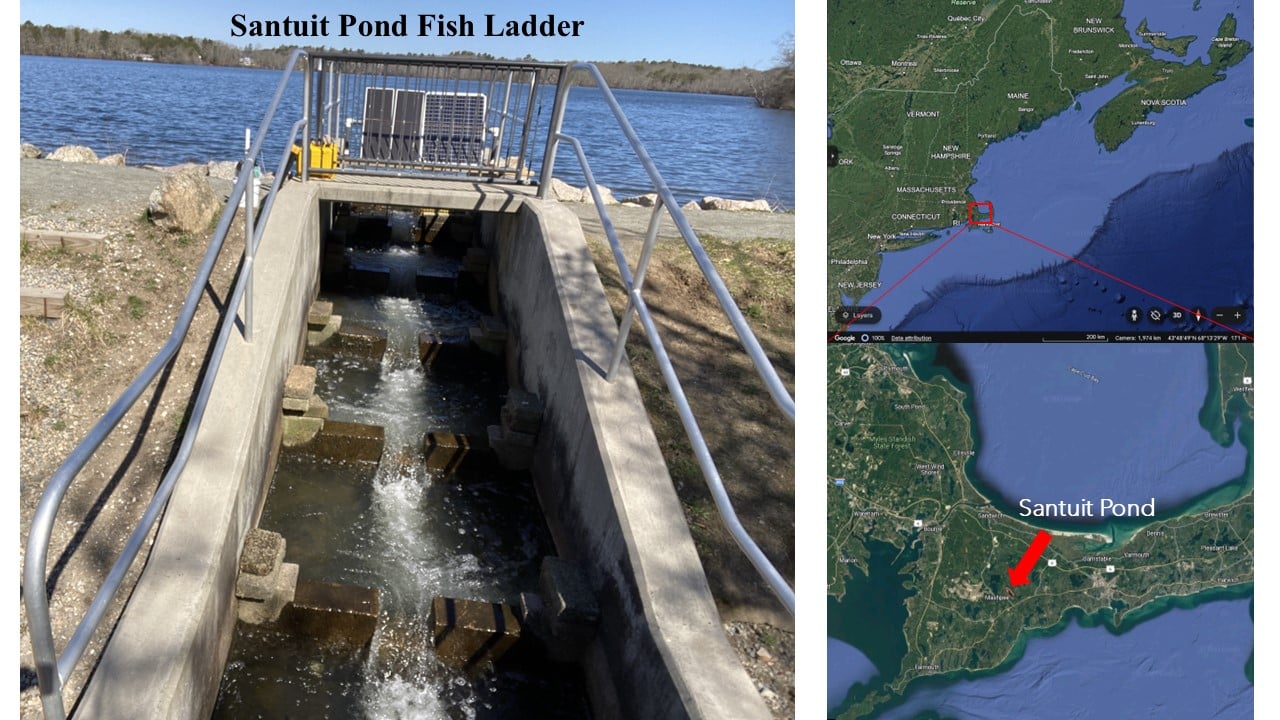

Research area

Top: Alewife and Blueback river herring, photo by Mike Scherer. Above: Camera trap set up by the fish ladder at Santuit Pond, photo by Kevin Bennett

Our Work

Our project combines cutting-edge technology and community collaboration to monitor river herring populations efficiently and accurately. Using underwater camera traps, we capture 24/7 underwater video footage of river herring during their spawning migrations. Leveraging AI and deep learning models developed in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) CSAIL department and MIT Sea Grant program, we develop programs to detect, track, and count the fish from collected videos.

Camera trap setup at Coonamessett River for collecting underwater videos. Photo by Zhongqi Chen.

Our work is currently based on three rivers, with key local partners on each: the Ipswich River with Ipswich River Watershed Association, the Santuit River with the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, and the Coonamessett River with Coonamessett River Trust. Community scientists, who have conducted river herring monitoring through streamside counts and tagging for over a decade, play a vital role by providing data for validating our AI models, making this project a collaborative effort.

Trapping river herring for tagging. Photo courtesy of Zhongqi Chen.

Impact

Our automated video collection and AI-powered monitoring system significantly reduces the need for human labor and associated resource investments, making conservation programs more sustainable and scalable. By deploying underwater camera systems in the Ipswich, Santuit, and Coonamessett Rivers, we have established a foundation for continuous data collection throughout the entire herring migration season. The AI-powered system has demonstrated greater precision in counting, providing reliable data for assessing population sizes. This infrastructure captures data that was previously unattainable through manual methods. The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) described the fish-counting technologies leading up to this project in a 2024 newsletter.

Our project goal is to serve as a feasible example and promote the adoption of advanced technologies to the broader fish conservation community. By showcasing the effectiveness of AI and automated monitoring, we hope to encourage other conservation programs to integrate similar technologies in their fish population monitoring and restoration efforts.

This project is funded by the MIT Sea Grant program, Coonamessett River Trust, Ipswich River Watershed Association, and the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe.