Here’s how climate change is affecting hurricane season

Rising global temperatures have created the conditions for deadlier storms

Satellite imagery of the 2016 Hurricane Matthew.

photo by Joshua Stevens/NASA Goddard

Hurricane season in North America is underway. Already, the second storm of the year to earn a name, Beryl, has cut a destructive swath across the Caribbean and the United States. This year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasted an extremely active hurricane season, anticipating between 17-25 named storms (the average is 14) and 4-7 major storms (average is 3) that reach category 3 and above with wind speeds exceeding 111 mph.

Intense seasons like this are likely to be a more common occurrence in a warmer world, as higher temperatures, rising seas, and changing weather patterns create the conditions for bigger, more destructive, longer lived, and more rapidly strengthening storms. Here’s how climate change is affecting the Atlantic hurricane season:

1. Higher temperatures mean more energy to form hurricanes

To understand how hurricanes are being affected by climate change, it’s important to understand how hurricanes are formed. They are essentially clusters of thunderstorms, building strength as they sweep westward using the energy from warm tropical waters. Under the right conditions, the Earth’s rotation will cause the cluster to spin into a cyclone shape. Because heat is energy, increases in sea surface temperatures play a critical role in strengthening these storms.

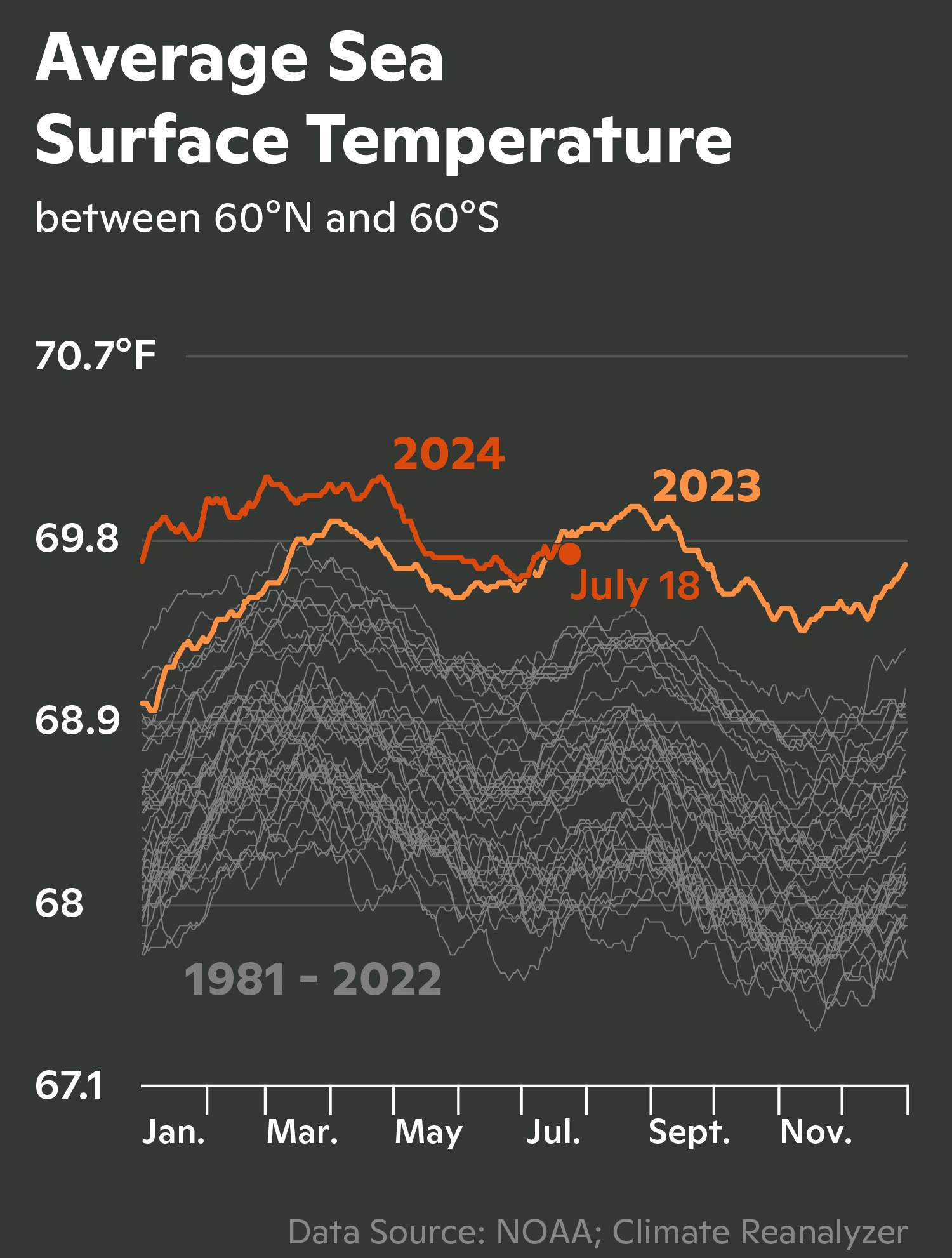

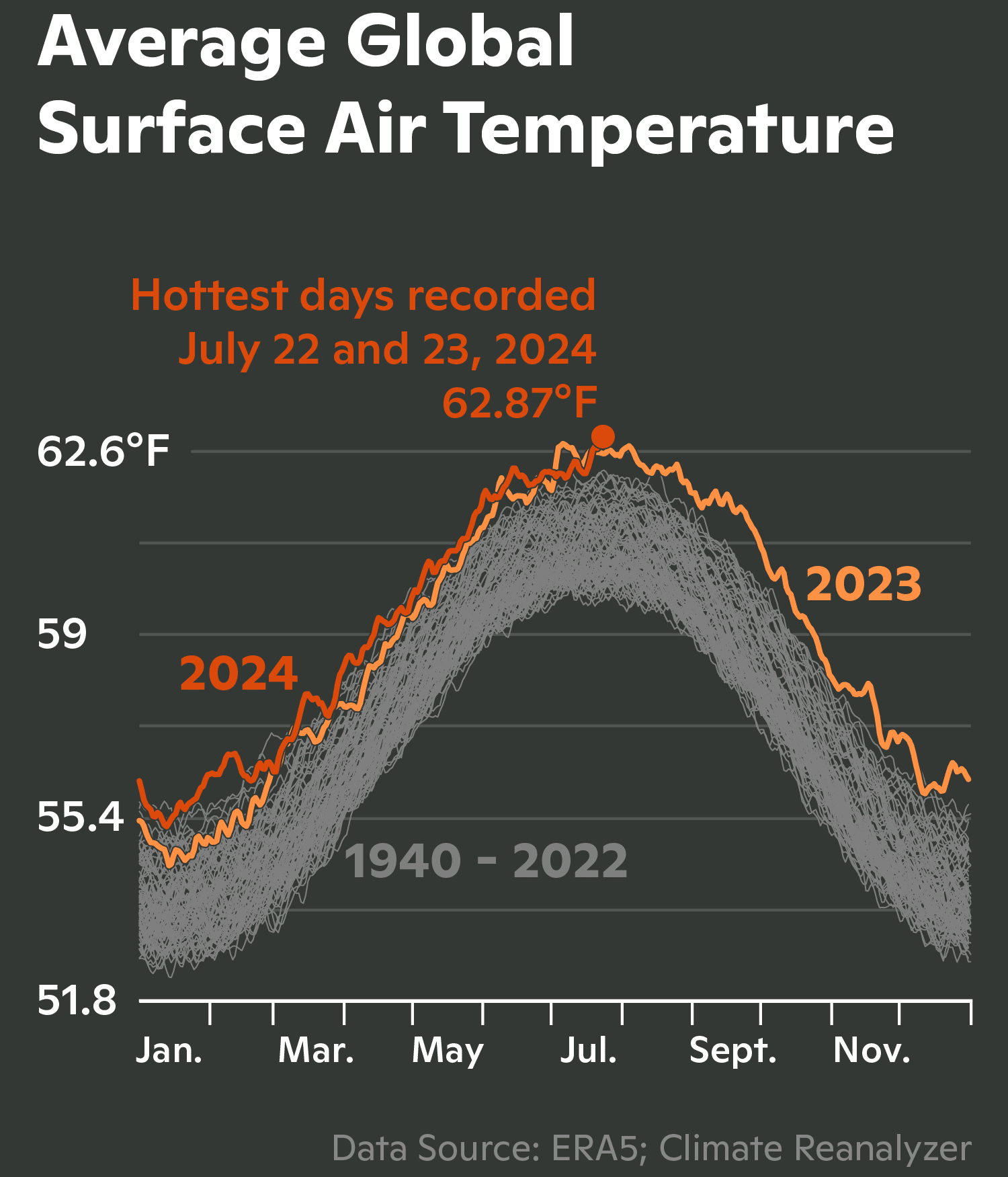

The ocean is a major heat sink for the planet, absorbing over 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gasses in the Earth’s atmosphere over the past few decades. Global sea surface temperatures have increased approximately 2.8°F since the beginning of the 20th century, and ocean heatwaves—large areas of above-normal temperatures that can last for months—are much more common and widespread. A hotter ocean means there is more energy available to fuel tropical storms, ultimately making it a more destructive event when it hits land.

graphic by Christina Shintani

2. The hotter the air, the more water it can hold

The second thing a hurricane needs to form is moisture. Water is evaporated and pulled up into the developing storm as it spins across warm waters of the tropical Atlantic. Hotter air temperatures mean more moisture can be held as vapor in the atmosphere, which allows storms to ingest greater amounts of water that will eventually condense into clouds and be released as rainfall. Condensation also releases heat into the storm, fueling its intensification. Models estimate that human-caused global warming has increased hurricane extreme hourly rainfall rates by 11%.

graphic by Christina Shintani

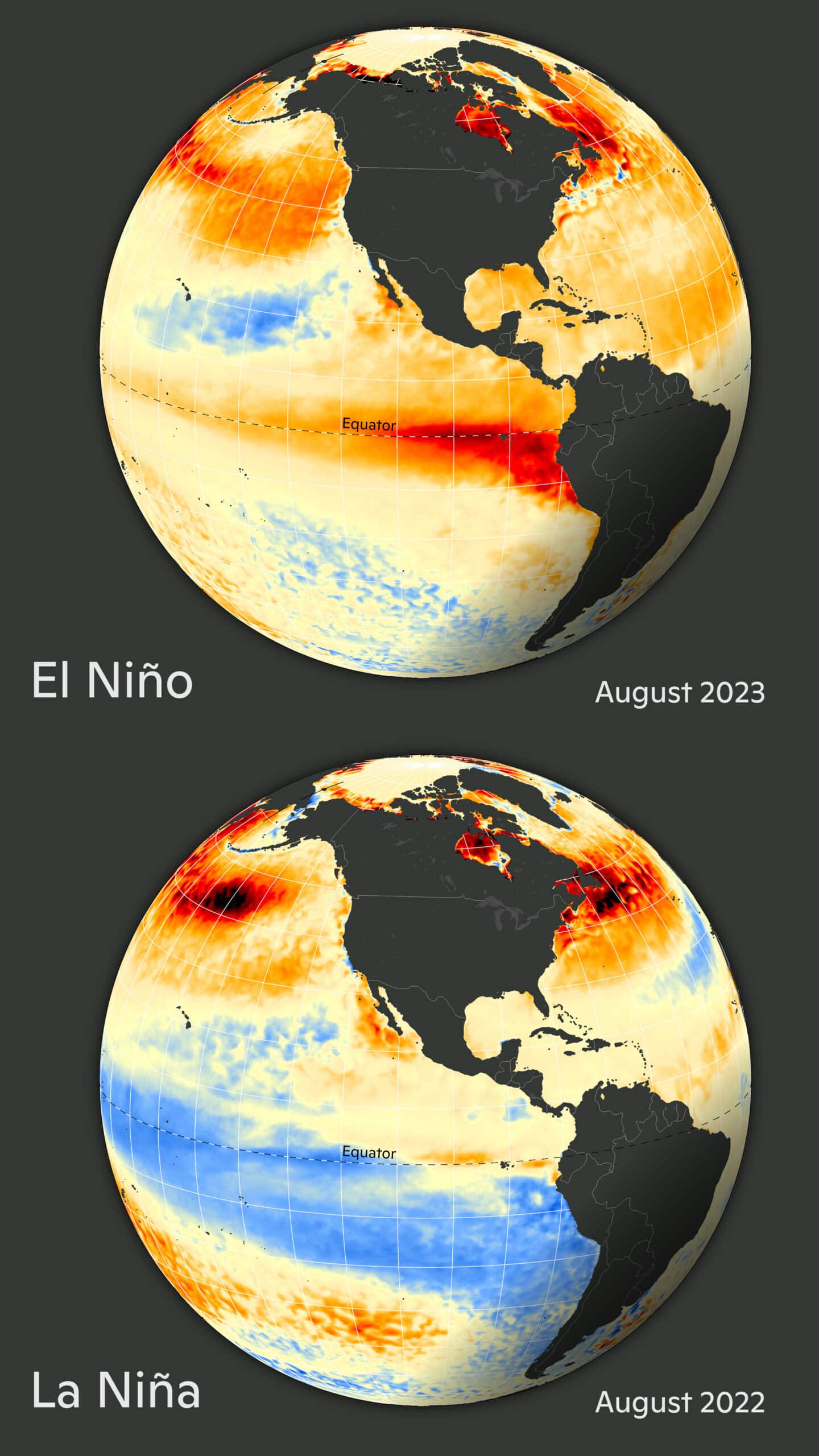

3. ENSO fluctuations are becoming more extreme

Typical sea temperature patterns for El Niño and La Niña.

maps by Greg Fiske

Climate change is also contributing to larger swings between the two phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)—meaning stronger versions of both El Niño or La Niña patterns. Currently, the Atlantic is headed towards a La Niña, which favors hurricane formation because it lessens vertical wind shear. Differences in wind speeds at different heights in the atmosphere can tear a storm apart, while less shear (more consistency in wind speeds between altitudes) allows storms to stay together and build strength.

Sea temperatures can signify ENSO patterns. This animation shows changes in temperature as 2024 moves into a La Niña.

animation by Greg Fiske

4. Tropical storms are undergoing rapid intensification more frequently

All these factors add up to more intense tropical storms in a world altered by climate change—meaning more category 3-5 storms and more big storms back-to-back. Since 1975 the number of category 4-5 cyclones has roughly doubled.

animation by Christina Shintani

This doesn’t necessarily mean that there will be more hurricanes; however, the ones that do form can be bigger and cause more damage (on top of the already estimated $2.6 trillion in damages since 1980.) If anything, data shows a slight decrease in the number of storms, moving more slowly along their path and releasing extreme wind and rain over a single location for longer periods.

5. Rising sea levels are making hurricanes more deadly

Sea level rise due to climate change has also made hurricanes a more dangerous threat for more people. As sea levels rise, coastlines are put at increased risk of flooding.

Sea levels have risen roughly 8 inches since the late 19th century, and the rate of rise is accelerating as climate change worsens. When a hurricane makes landfall, water is pushed inland by high-speed winds in an event known as storm surge. Every additional inch of sea level rise allows the surge to travel farther inland, threatening a wider area and causing more damage, death, and injury. This is especially true in areas where increasing human development along the coast has exposed more people and homes to greater risk.

map by Christina Shintani

As temperatures continue to rise, communities along the East and Gulf coasts can expect to be hit harder by destructive storms. Despite this, more and more people are choosing to live and build near the shore, increasing the cost of damages when hurricanes strike. Slowing warming temperatures and building adaptation measures to protect coastal communities will become more urgent as Atlantic hurricanes intensify.